Backstory: The Story Behind Chris Orcutt’s The Man, The Myth, The Legend

Between 2010 and 2011, I wrote over thirty short stories, many of which appeared in The Man, The Myth, The Legend or as chapters of the novel One Hundred Miles from Manhattan.

Between 2010 and 2011, I wrote over thirty short stories, many of which appeared in The Man, The Myth, The Legend or as chapters of the novel One Hundred Miles from Manhattan.

Back when I was writing them, I was still pursuing publication for them in magazines, including what I then considered the crème de la crème of magazines, the New Yorker. I would write a draft of a story, let it sit in a drawer for a few weeks, revise it, let it sit again, revise it again, and submit it. Alas, the New Yorker never did publish any of them, although they did graciously send me a few personal rejections that proved someone had at least read the stories, enjoyed them and given them serious consideration.

But I digress. Let me tell you about the magical spring and summer of 2010, during which I wrote the bulk of the stories in The Man, The Myth, The Legend. I couldn’t stop coming up with ideas. I would wake in the middle of the night and have to go out to the living room so I could scribble out whole passages that poured out of me.

The characters’ voices, the situations, the story concepts—everything came to me complete, fully formed. Indeed, for most of the stories in The Man, The Myth, The Legend, there were very few changes between the first draft and the final, published story. Ultimately I consider these stories to be a triumph of voice; the voice of each narrator is clear, distinct and compelling.

Around the time that I was writing the stories, the “mash-up” hack author Seth Grahame-Smith was making some noise because he’d either just released Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, or it’d been announced that it was being made into a movie. This incensed me. First of all, the notion that this clown had had a bestseller using a story and characters that weren’t his, and that the original author, Jane Austen, had been completely unknown when she died, filled me with bile. And that’s when the idea for my story “The Magnificent Murphy” came to me. Fueled by hatred for this idiot, I wrote the first draft of “The Magnificent Murphy” in one day—all 5,000-some-odd words.

Having read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby over two dozen times, I had an instinctive feel for the diction, syntax and sentence rhythms of the book. I started to think, “What if the narrator, Nick Carraway, hung out with someone else besides Gatsby, Tom and Daisy that summer, and what if this someone else was the original “mash-up” novelist, a guy named Martin Michaels-Murphy?”

Having read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby over two dozen times, I had an instinctive feel for the diction, syntax and sentence rhythms of the book. I started to think, “What if the narrator, Nick Carraway, hung out with someone else besides Gatsby, Tom and Daisy that summer, and what if this someone else was the original “mash-up” novelist, a guy named Martin Michaels-Murphy?”

In college, I had known a poseur, a would-be “writer” who had once, gesticulating in a café with an unlit pipe and while wearing a turtleneck and a tweed jacket with elbow patches, said to me, “Chris…I’m a writer. You seem like a sensitive fellow. You should be a writer, too.”

He said this not knowing that I already was a writer, that I wrote for the school magazine, that I’d written stories since I was 12 years old; but when he persuaded me and a pretty Jewish girl I was pursuing at the time to come back to his apartment (where he showed us scads of God-awful Italian sonnets that he had printed out in cursive font and taped to the plaster walls), I resolved to one day lampoon him in literature.

Which I most willingly, and most scathingly, did withal, in “The Magnificent Murphy.” The character of Murphy lives on the other side of Gatsby’s property, and the story, told from Nick Carraway’s POV like Gatsby, is about the adventures Nick has that summer with Murphy. I’m proud of this story. When I’ve reread it, I’ve found it so good that it’s hard for me to believe that I wrote it. With certain sentences, I just know I nailed the voice of Nick Carraway:

Early in my residence at the mean little bungalow that quaked in the shadow of Gatsby’s mansion like a tick beneath a Burmese elephant…

As I said earlier, everywhere I went that spring and summer, and everything I did, inspired another story. My wife and Muse, Alexas, and I were in the grocery store cereal aisle one evening when I got the idea for “Seven Whole Grains on a Mission™.” There was almost no Kashi cereal on the shelves, about which I remarked, “What is this, the Soviet Union?”—to which my brilliant wife said, “Hmm…they’re probably busy out trying to find that elusive eighth grain.”

Alexas’s words hit me like a thunderclap. I stood dumbfounded in the aisle for several minutes as the entire story of a James Bond-like Global Grain Explorer (GGE7) played in my head. He trekked through the mountains of Pakistan and Afghanistan trying to find the mysterious, super-salubrious, and possibly apocryphal, “spillit” grain. I pulled out my pocket Moleskine notebook and wrote the opening lines of the story right there in the aisle, and I finished the first draft of it the next day. My favorite sentence in the story comes during the climax:

Alexas’s words hit me like a thunderclap. I stood dumbfounded in the aisle for several minutes as the entire story of a James Bond-like Global Grain Explorer (GGE7) played in my head. He trekked through the mountains of Pakistan and Afghanistan trying to find the mysterious, super-salubrious, and possibly apocryphal, “spillit” grain. I pulled out my pocket Moleskine notebook and wrote the opening lines of the story right there in the aisle, and I finished the first draft of it the next day. My favorite sentence in the story comes during the climax:

Their body parts were dashed across the field like exploded bits of the ripe real strawberries in our TLC soft-baked cereal bars.

Another of my favorite stories in The Man, The Myth, The Legend, “The Man Behind the Signs,” also came to me when I was with my Alexas. She was driving us into work one morning, and we passed through a construction zone. I remarked about one of the signs, saying, “You know…somebody writes those things. What about a story from the POV of a road sign engineer?” When Alexas chuckled, I knew I had a winning idea, and as soon as I got to my spot in the Vassar Library, I started writing the story.

“The Dogcatcher” came to me after having seen a ton of “LOST DOG” flyers around Eastern Dutchess County for some reason. I thought about all of these dogs lost out there, and the fact that many of these dogs came from upscale Millbrook. Then I thought about how communities used to hire dogcatchers, and then I thought about how much I loved the voiceover narration in my favorite noir movies, and I imagined this neo-noir independent dogcatcher out there, finding the dogs of wealthy people and making big bucks doing it.

A couple years earlier, while foisting a bunch of Thomas Kinkade “paintings” on a Vermont couple that owned a B&B, I had written the opening passage and part of a scene with the wealthy, beautiful dame “client,” so all I had to do was dig out that notebook and continue the story. My favorite passage in the story is its opening:

It was one of those mid-October afternoons in the Hudson Valley when the foliage is so brilliant it hurts your eyes. I wore Armani sunglasses and, with the snap in the air, my Orvis leather flight jacket. Back in my closet I had a great suit—a Hickey Freeman that cost me two grand—but in this business, first impressions are everything, and the worn leather jacket says you’ll stick.

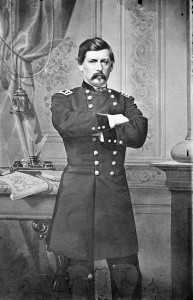

I’m not exactly sure how “The Lost Dispatches of General George B. McClellan” came to me. I know that I stumbled upon a copy of McClellan’s autobiography, and when I read sections in it, I was simultaneously amazed and horrified by McClellan’s pomposity and self-deception. I thought to myself, “What if these telegrams and letters were just the tip of the iceberg? What if the really crazy stuff had been hidden all these years, and a story revealed these lost dispatches?”

I’m not exactly sure how “The Lost Dispatches of General George B. McClellan” came to me. I know that I stumbled upon a copy of McClellan’s autobiography, and when I read sections in it, I was simultaneously amazed and horrified by McClellan’s pomposity and self-deception. I thought to myself, “What if these telegrams and letters were just the tip of the iceberg? What if the really crazy stuff had been hidden all these years, and a story revealed these lost dispatches?”

Like with “The Magnificent Murphy,” I was astounded by how easily I was able to adopt McClellan’s voice—after reading only a small portion of his maundering and otherwise forgettable autobiography. Here is my favorite sentence from the finished story (McClellan writing to President Lincoln):

As you can imagine, Sir, bacon is the coin of the realm in these parts.

The last story in the collection I’ll mention here is “The Last Great White Hunter.” For a few weeks prior to writing it, I was reading a bunch of “armchair safari” books for some reason (not sure why; it was hot that summer and I was wearing a safari jacket most days), including Robert Ruark’s classic, Use Enough Gun. I began to seek out a genre: the African safari spoof. Discovering there was no such genre, I decided to write it.

I envisioned the first part of the story being told by a deep-voiced omniscient narrator (like Anchorman narrator Bill Kurtis). In the opening, the narrator relates the legend of Buck Remington, after which the story slides into Buck’s POV. Suddenly a passage came to me, a passage that I want etched on my gravestone (or on a plaque, if I get my wish and my ashes are entombed in the floor of Vassar’s Thompson Library a la Westminster Abbey) as my own epitaph:

I envisioned the first part of the story being told by a deep-voiced omniscient narrator (like Anchorman narrator Bill Kurtis). In the opening, the narrator relates the legend of Buck Remington, after which the story slides into Buck’s POV. Suddenly a passage came to me, a passage that I want etched on my gravestone (or on a plaque, if I get my wish and my ashes are entombed in the floor of Vassar’s Thompson Library a la Westminster Abbey) as my own epitaph:

What kind of a man was he?

More than a man’s man, that’s for sure.

He was a man’s man’s man.

I love all the stories in this collection, and although the story behind “The Bootlegger,” for example, is another interesting one (my paternal grandfather, who, for a short time bootlegged whiskey from Canada, was the inspiration for this character), I won’t discuss it in detail here.

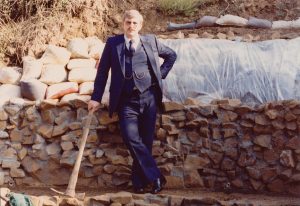

Joe’s litigator headshot.

On May 23, 2018, an ardent fan of these stories died. My father-in-law, Joseph Kubancik, had been a fan of my books going back 20 years, when I came out with my first novel, Nick Chase’s Great Escape.

Joe had a great sense of humor and a terrific wit. Early on in my courtship of his daughter, Joe and I discovered that we shared a love of movies and Sherlock Holmes lore. His favorite movie was Field of Dreams, and his favorite singer-songwriter was Harry Chapin.

Joe had kept all of my books (along with those of only one other author) on a shelf in his bedroom. Knowing how much he enjoyed these stories, and knowing he was dying, back in early May I changed the book dedication to him:

For Joseph Kubancik,

an ardent fan of these stories

and the rarest of men:

A kind father-in-law,

A loving father,

An honest lawyer,

And a good human being.

Before you fade into the cornfield,

know that you will be remembered.

Thank you, Joe.

Following is the obituary I wrote for Joe:

Joseph J. Kubancik, a distinguished Bay Area litigator for 35 years, died at his Oakland, CA home on May 23 after a short illness. He was 73.

Born March 20, 1945 in Cleveland, OH, Kubancik graduated from St. Joseph’s High School in 1963. A Vietnam veteran, he served in the U.S. Air Force in Ankra, Turkey and Da Nang, Vietnam. He was honorably discharged in 1967, after which he attended the University of San Francisco, graduating in 1970.

Kubancik received his J.D. law degree from Golden Gate University, where he was also editor of the law review, and his L.L.M. degree from the University of Texas Austin. He was admitted to the State Bar of California in 1974, and became an accomplished civil litigator.

Beyond his work as an attorney, Kubancik was most proud of being a father to his three daughters. Whether driving them to dance rehearsals or swim meets, building theatre sets or cabins at their summer camp, or working in retirement for his eldest daughter at Every Dog Has Its Daycare in Oakland, CA, he was actively involved in their personal, creative and professional pursuits.

Kubancik, who donated his body to the USCF medical school, is survived by his three daughters, Mischa Arp of San Francisco, CA; Alexas Orcutt of Millbrook, NY; and Katherine Culhi of San Diego, CA.

Comments (0)