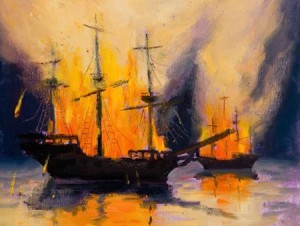

Burning Your Ships

A while back, I got in an online argument with another writer.

He was proffering financial advice to writers, in effect saying this: “I made $164,000 last year as a writer, but I’m the exception, so whatever you’re doing now to earn a living, don’t quit your day job.”

The originality of his message blew me away. I’d never heard such a thing before! “Don’t quit your day job.” So simple, so pithy, so elegant! I repeated it to myself over and over so I wouldn’t forget it. Whenever I encountered fellow writers, whether they were bestselling authors, bloggers or Starbucks poets, I said to them, “Don’t quit your day job.” They all frowned and shoved me away (I’m talking to you, Stephen King).

Seriously, I did none of those things. Instead, because $164,000 Guy’s draconian pronouncement was so antithetical to my approach to Life and my writing, in the interest of fostering lively debate on this issue, I posted a respectful critique of his position, thinking he’d appreciate one of his readers taking the time to do this.

BIG MISTAKE. Turns out, $164,000 Guy was more interested in being RIGHT than he was in finding the truth (a shocker, I know), and immediately countered with a half-assed response, which I won’t dignify here. Bottom line: I decided that instead of wasting my time on a pointless debate, I was just going to keep writing. It’s like Hemingway said in an interview late in his writing career:

When I was a young writer, the debate was this: ‘altogether’ or ‘all together’—should it be one word or two? How’d that turn out anyway?

Interesting thing about the writing world: it’s full of clowns like $164,000 Guy—people who suggest that they’re the only ones who were born to write, that they somehow are the only ones graced by Providence with the requisite confidence, talent, patience and persistence to make a living as a writer.

Back in college, one of the best courses I took was “Explorers of the World,” taught by a historian who had been to the South Pole and the top of K2. And when she talked about the Spanish conquerer/ explorer Cortez, the woman lit up. Her favorite anecdote, and mine, was how, upon arriving in the New World, to motivate his men, Cortez burned his ships. You’ve probably heard this story, so I won’t belabor it here. But in case you don’t know it, here’s an excellent blog entry about it written by a 3‑time world wrestling champion.

I came to love this principle of “burning your ships,” and I’ve applied it liberally in all of my endeavors, including writing. For 15 years after college I held day jobs as a high school history teacher, technology manager in financial services, web content editor and adjunct English professor. Eventually, however, I noticed that my day jobs stole too much of my time and sapped too much of my energy. I had to make a choice. I chose to be a full-time writer. I make between $75 and $100 per hour as a scriptwriter and speechwriter for corporations, but I would never have been able to make that kind of money if I’d stayed on the “safe” amateur track.

Going pro has also improved my own writing—my fiction. This isn’t to say that it’s always easy. On the contrary, there are many months when I just squeak by financially. But I gotta tell you, knowing that there are no ships waiting in the harbor to take me back, knowing that there’s no “fallback position,” has motivated me like you wouldn’t believe. There’s no going back. There’s only FORWARD. Forward or die. Now, I’m not saying that “burning your ships” should necessarily manifest itself as quitting your day job. Ultimately it’s about making a choice: a choice towards writing or something else. It’s a question of commitment.

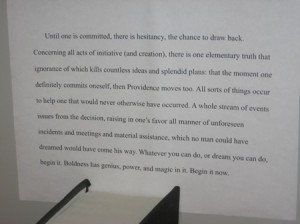

For years, I’ve kept only one quote above my desk. While the words have been alternately attributed to German writer/philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Scottish explorer W.H. Murray, exactly who said them isn’t very important. What is important is their message, and their message is clear and simple: COMMIT.

Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back. Concerning all acts of initiative (and creation), there is one elementary truth that ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favor all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamed would have come his way. Whatever you can do, or dream you can do, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it. Begin it now.”

The other thing that rankled me about $164,000 Guy’s message of “don’t quit your day job” is the double standard with which it’s applied. People with “safe” day jobs (by the way, do these exist today?) are told not to quit them to be writers or artists, yet this same advice is never given to people who show promise as writers and artists and express an interest in, say, computer programming.

Implicit in this assumption is the idea that only creative endeavors carry the risk of failure. Not so. Talk to Mark Twain. Ask him how that opportunity with the Paige Compositor worked out for him.

You know what? Not so much for him with the business stuff.

Here’s a great line from John Gardner’s On Becoming a Novelist on this subject:

But anyone embarking on a career, or pursuing a calling, risks setback and failure. There are failed policemen, politicians, generals, interior decorators, engineers, bus drivers, editors, literary agents, businessmen, basket weavers.

To live—really live—means risking failure. Consider all that might not have been had some of our greatest creators stuck to the “safe” road:

- What if Bill Gates hadn’t dropped out of Harvard to found Microsoft?

- What if Einstein had remained a patent clerk?

- What if Jane Austen hadn’t written her marvelous novels?

- What if Sting had remained a schoolteacher?

- What if Robert Frost had said to hell with poetry and instead spent all his time farming, like his forebears?

The other fallacy embedded in $164,000 Guy’s argument is the idea that, unlike every other profession, writing is one in which you can become great without total commitment. This is just ridiculous. There’s an old joke among writers. Maybe you’ve heard it. It goes like this:

A published novelist goes to a heart surgeon for some tests. During the exam, the doctor says, “Hey, could you give me the name of your publisher?”

“Sure, why?” replies the novelist.

“Well, I have a six-month sabbatical coming up, and I’d like to write a novel and see it published.”

The novelist thinks about this for a moment before replying.

“Sure, sure,” the novelist says, “I can do that. But do me a favor, will you?”

“Name it,” the doctor says.

“Well, I have six months free myself, and I’ve always wanted to perform open-heart surgery. Could you talk to your hospital and set something up for me?”

The moral is clear: Being a writer requires the same, if not more, commitment, self-discipline, education and training as any other profession, and to think that you can become a master writer without a complete commitment is self-deception of the highest order.

Here’s what one of my writing heroes, the brilliant David Mamet, had to say about the subject. The following quote is from one of his many excellent books of essays—True and False: Heresy and Common Sense for the Actor :

Those with “something to fall back on” invariably fall back on it. They intended to all along. That is why they provided themselves with it. But those with no alternative see the world differently. The old story has the mother say to the sea captain, “Take special care of my son, he cannot swim,” to which the captain responds, “Well, then, he’d better stay in the boat.”

Whether or not you burn your ships, and exactly what that means, is up to you. All I can say is, if you believe you’re holding yourself back with fallback positions, contingency plans or plain old ships, you gotta burn ’em. Light ’em up.

Pingback: “It Takes All Kinds” or “Maybe You Can’t Design” - SilverPen Publishing