My Favorite Books: Hemingway’s A MOVEABLE FEAST

You know a book is a favorite of yours when you have multiple copies of it, and you find some of those copies in the oddest of places:

- under the couch

- in your field coat pocket

- under the car seat

- in the box of cat toys (cats, too, appreciate good literature)

- in a knapsack

- in the freezer (for real; inexplicably, I’ve also found my belt in there)

Over the years, I’ve had this experience with a few books, the most recent being Ernest Hemingway’s memoir, A Moveable Feast. While rereading it a few days ago, I had the serendipitous experience of finding five other copies around our small apartment.

Over the years, I’ve had this experience with a few books, the most recent being Ernest Hemingway’s memoir, A Moveable Feast. While rereading it a few days ago, I had the serendipitous experience of finding five other copies around our small apartment.

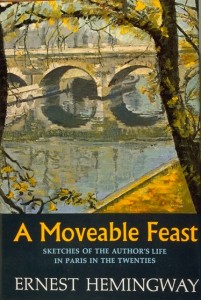

This is not meant to be a book review, nor is it “literary criticism” (I never got that stuff, and still don’t). That being said, for those of you who don’t know this book, here are the facts: It was published posthumously in 1964 to mixed reviews. It appeared first as a serial in Life magazine, then came out in the hardcover pictured below. Most importantly, as executor of his literary estate, Hemingway’s fourth (and last) wife, Mary, engaged in some significant editing of the final manuscript, cutting what many scholars believe were significant sections, including a long apology to his first wife, Hadley, for leaving her.

Many scholarly articles have been written about the version of this book that “might have been,” but as insightful as they may be, I’ve never read any of them. Besides, I’m not a scholar. Never liked school much. Tended toward autodidacticism. Like Mark Twain said, “I never let schooling get in the way of my education.”

But I digress. In plain, honest, regular English, not academese, let me tell you why A Moveable Feast may just be my favoritest (grammatically incorrect for emphasis) book of all time.

At least once a year since I was 17, I have read this memoir of Hemingway’s early life as a writer in Paris. That’s cover-to-cover reading. I couldn’t even count the number of times I’ve opened it just for inspiration. The opening alone gets me every time:

Then there was the bad weather. It would come in one day when the fall was over. We would have to shut the windows in the night against the rain and the cold wind would strip the leaves from the trees in the Place Contrescarpe. The leaves lay sodden in the rain and the wind drove the rain against the big green autobus at the terminal and the Café des Amateurs was crowded and the windows misted over from the heat and the smoke inside.

Not bad, right? For me, it’s the first sentence—“Then there was the bad weather.” This is a perfect example of Aristotle’s admonition to begin stories in media res (in the middle of things). Starting out with “Then there was the bad weather” immediately begs the questions of, “Well, what happened before…before the ‘then’? What was the fall like? What happened?” By raising these questions with the first sentence, Hemingway also creates narrative drive, which I’ve written about in greater detail elsewhere.

It’s the language that makes me read this book so often. The lyrical nature of the prose borders on hypnotic. Yet it’s other things, too, like the evocation of place, and the voice, and the precise details. The bottom line is, what the narrator Hemingway does throughout the book isn’t very important; it’s how he does it, the combination of all of the above—the style—that pulls you along helplessly.

In the spring mornings I would work early while my wife still slept. The windows were open wide and the cobbles of the street were drying after the rain. The sun was drying the faces of the houses that faced the window. The shops were still shuttered. The goatherd came up the street blowing his pipes and a woman who lived on the floor above us came out onto the sidewalk with a big pot.… I went back to writing and the woman came up the stairs with the goat milk.

Every time before I begin a new project, or if I’m in the dumps about a current one, I’ll grab a copy of AMF out of the freezer and open it to one of my favorite passages.

As a rule, I don’t care for audiobooks, but I bought this one and copied the entire thing over to my iPod. I play it during my long walks through the Millbrook countryside, letting Hemingway’s elegantly simple, detail-driven prose seep into me. It’s a blustery autumn day out there today, a lot like Hemingway himself describes in his story, “The Three Day Blow,” and I think I’ll take a walk later and listen to AMF as the wind shakes the leaves from the trees.

I believe this book is an absolute necessity for writers, for buried within Hemingway’s descriptions of cafés, horse-racing and exotic cocktails are dozens of gems about the craft of writing, like this one…

It was wonderful to walk down the long flights of stairs knowing that I’d had good luck working. I always worked until I had something done and I always stopped when I knew what was going to happen next. That way I could be sure of going on the next day. But sometimes when I was starting a new story and I could not get it going, I would sit in front of the fire and squeeze the peel of the little oranges into the edge of the flame and watch the sputter of blue that they made. I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, “Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.” So finally I would write one true sentence, and then go on from there.… If I started to write elaborately … I found that I could cut that scrollwork or ornament out and throw it away and start with the first true simple declarative sentence I had written. Up in that room I decided that I would write one story about each thing that I knew about. I was trying to do this all the time I was writing, and it was good and severe discipline.

As epigrams on writing go, “…write one true sentence” has been profoundly over-quoted, when most of the people who mention it don’t know what the hell it means. I’ve meditated on it like Kant meditated on Hume, and I’m not sure I get it either.

One couplet of Hemingway’s in particular has occupied my thinking on and off for weeks, and that’s this: “What did I know best that I had not written about and lost? What did I know about truly and care for the most?” I believe those two questions, more than any other two that I’ve read, contain some of the best advice to writers—especially struggling novices, like I was when I first read them.

A Salon.com travel writer, Don George, eloquently describes his attachment to A Moveable Feast in this article. However, the passage I like the most is one in which he gets to heart of the book—its poetic and nostalgic (but not sentimental) recollection of a simpler time in a man’s life, before his senses were dulled and his passions quashed by practicality:

Doubtless you have your own Paris…it’s the place where life first came vividly to bloom for you, where you walked out the door and fell in love, where you couldn’t believe the exquisite beauty of the buildings, or the clouds, or the sun that shone after the rain.

For me, that place was, and will always be, Boston, where I fell in love with the Red Sox as a boy and where I went to college, where I dated many pretty (and a few crazy) women, where I smoked cigarettes and marijuana and drank, and listened endlessly to The Doors, and stayed up all night, unmedicated and unstable and loving it. I’d tell you more about those days, but sorry, I’m writing about them elsewhere now.

Comments (3)