My Prodigiously Convoluted Yet Miraculously Productive Low-Tech Writing Process — Part 1

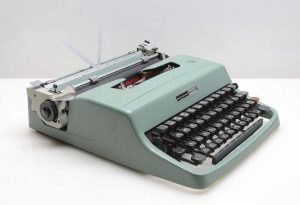

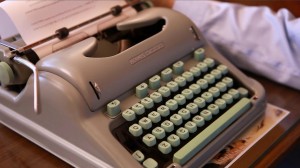

I’m writing this blog entry on my latest piece of low-tech equipment, an Olivetti Lettera 32 typewriter. All told, I now have six typewriters:

• The Lettera 32

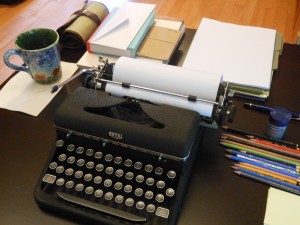

• A Royal Quiet Deluxe

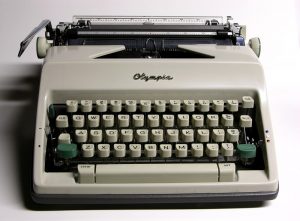

• An Olympia SM9 Deluxe

• An Hermès 3000 (Hermes, son of Zeus and Maia, is the messenger of the gods, and the god of merchants, thieves, and oratory. By the way, fellow typewriter folks, it’s pronounced “air-MEZ” not “HER-mees.”)

• An Olympia SG‑3

and

• An IBM Selectric III. (Although at times a gorgeous, high-maintenance bitch who reminds me of an old girlfriend from my early twenties, she is nonetheless the pinnacle of electromechanical engineering.)

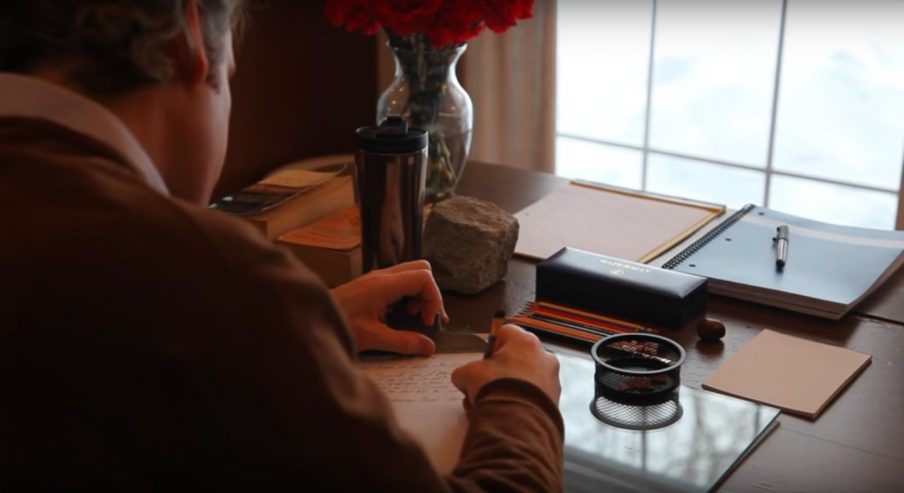

Typically, whenever I start a new piece of work—be it a novel, a story or even a blog entry—I write the first draft either on one of my typewriters, or in longhand in pen or pencil. My three preferred pens are 1. my MontBlanc 4810, 2. the Pilot Varsity disposable fountain pen, and 3. the Pilot Precise V7 RT.

As far as pencils are concerned, I’ve worked with at least 50 different brands and styles, and I’ve found these three to be the best: 1. the Palomino Blackwing 602, 2. the Palomino California Republic, and 3. the Mongol #2. Honorable mentions go to the Pilot G‑2 pen (black) and the Mirado Black Warrior #2 pencil.

Okay, so I write a first draft of my work in longhand or, as I’m doing now, on one of my typewriters. When the first draft is finished, I make a photocopy of it, store the copy in the trunk of my car, and the original in a drawer. I then move on to something new.

The Drawer Method

When I was in college, one of my philosophy professors introduced me to a step I could integrate into my writing process that would enable me to gain some distance from what I’d written and see ways to improve a piece of writing when I returned to it. I’ve been using this idea for 25 years, and it’s never failed me.

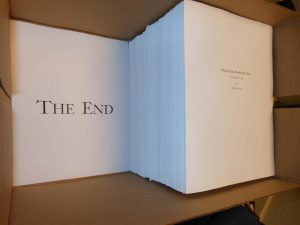

When I finish the first draft of a piece of writing, I box it up, put it in a drawer and forget about it for a while. Depending on the length and complexity of the work, “a while” can range anywhere from a couple of hours to several months or years. The key is to literally put the work in a drawer, close the drawer and forget about it. Even though the writing is out of your purview, your subconscious will continue to think about it, solving problems it knows are there.

When I finish the first draft of a piece of writing, I box it up, put it in a drawer and forget about it for a while. Depending on the length and complexity of the work, “a while” can range anywhere from a couple of hours to several months or years. The key is to literally put the work in a drawer, close the drawer and forget about it. Even though the writing is out of your purview, your subconscious will continue to think about it, solving problems it knows are there.

Also, by leaving the writing alone in the dark of a drawer (or in a box in the closet, if the draft is 1,600 pages long, like my latest novel), a mysterious germination process occurs, such that when you return to the work, passages that you thought were dead ends now sprout green tendrils.

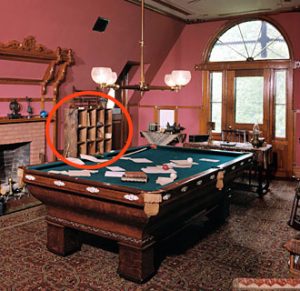

Obviously I’m not the first writer to put work away for a while, in order to return to it with a refreshed perspective. Mark Twain, for example, kept pigeonholes in the writing room of his Hartford, CT house. Whenever he was hopelessly stalled on a book or story, he would tuck the manuscript in one of the pigeonholes to allow “the well to fill up again,” and pull down another manuscript and begin working on that one again.

Obviously I’m not the first writer to put work away for a while, in order to return to it with a refreshed perspective. Mark Twain, for example, kept pigeonholes in the writing room of his Hartford, CT house. Whenever he was hopelessly stalled on a book or story, he would tuck the manuscript in one of the pigeonholes to allow “the well to fill up again,” and pull down another manuscript and begin working on that one again.

The Blue Pen

So, my work has lain in a drawer for a while. For me, “a while” is usually a few months. When I finish the first draft of something else and go to put it in a drawer or the closet, I’ll look at the other books or stories already in there and ask myself if I think they’ve lain dormant long enough. (Right now, for example, I have the 1st or 2nd drafts of four books and a dozen stories in drawers or my closet.)

Sometimes I’ll read the first sentence or the first page to see if it catches my interest or surprises me in some way. The best sign that the work is ready to come out of the drawer (or the closet; ha, ha) is this: I start reading it and, because enough time has passed that I’ve forgotten the details, I get swept up in the story. I might even find myself smiling or laughing, etc. If this happens, I’ll take the book/story/essay out of the drawer and read it straight through. The only notations I’ll make on the manuscript during this read are “!” to denote sections I really like, or “zzzz” in places where things bog down. The “zzzz” chapters, passages or sentences become candidates for cuts during the next read.

At this point, it’s time for a blue-pen read. I read the entire thing again, but much more slowly, making marks in the text and margins with a blue Pilot Precise V5 pen. Many of these marks are insertions or rewordings of the text on the page. The marked-up manuscript then goes back into a drawer to “recuperate” from the trauma of revision.

At this point, it’s time for a blue-pen read. I read the entire thing again, but much more slowly, making marks in the text and margins with a blue Pilot Precise V5 pen. Many of these marks are insertions or rewordings of the text on the page. The marked-up manuscript then goes back into a drawer to “recuperate” from the trauma of revision.

Typing It Into a Word Processor

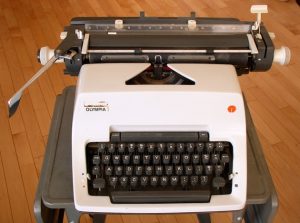

When I take out the marked-up manuscript again (usually within a couple weeks of edits), it’s time to type the revised text into a word processor. For many years, this meant I would fire up Microsoft Word and type the marked-up manuscript into the computer. However, after better than two decades of doing it this way, I discovered that Word and the computer’s internet connectivity were too distracting.

Recognizing this, four years ago I set up a “Writing Only” account on my MacBook Air (with the internet disabled) and would type into MS Word that way. But even this I found distracting; Microsoft Word, with its endless varieties of fonts, screen layouts, and those annoying green or red squiggly lines that appear under words and sentences, constantly inveigled me to play with Word’s many “time-saving features,” when all I really needed to do at this point was get the goddamned words typed in.

That’s why I decided in January of this year to start using a dedicated word processing tool at this stage of my writing process.

And you can read it about next week, when I’ll describe this missing link for novelists and serious writers.

Comments (0)