My Prodigiously Convoluted Yet Miraculously Productive Low-Tech Writing Process — Part 2 — With a Few Modest Writing Secrets

In the first installment of this piece, I described the first half of my writing process:

- Writing the first draft in longhand or on a typewriter

- Storing the completed draft in a drawer

- Editing the hand- or type-written manuscript with a blue pen

- Retyping the manuscript into a word processor

Now, hold on to your hat as we go into the second half of this piece, starting with my recent discovery of the missing link for novelists and serious writers.

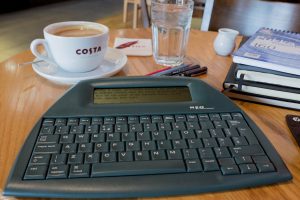

The Alphasmart Neo2

In January 2018, I made the decision to double-down on my low-tech method of working. As I saw it, the weak point in my writing production system was the computer. As far as writing books is concerned, the area in which computers shine is in editing and layout; you can move whole chapters and passages around, and prepare books for publication. But they are really only useful in the late stages of writing a book.

Let me emphasize something again: When writing a book, especially during the early drafts, it’s all about getting the words written—the raw words, without worrying about fonts, how the text will “look on the page,” or any of those aesthetic concerns.

Knowing this, I wanted a distraction-free word processor that would enable me to get the words typed up as efficiently as possible.

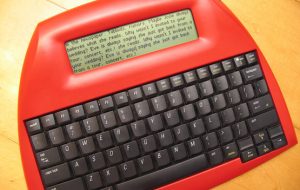

While doing some research, I found a clunky hipster writing affectation (pictured at right), the Freewrite, which, at $500, was as expensive as it was pretentious. But then I found an older word processor, no longer in production anymore, the Alphasmart Neo.

I was instantly smitten.

It seems that the Neo, Alphasmart 3000, and Neo2 were designed originally for the education market, to teach students how to type. Many schools couldn’t afford to outfit every student with a computer, but, at about $200 a unit (back in the early 2000s), the Neo was a great alternative. My sense is that when tablets became inexpensive, however, schools went with them instead of the Neo.

But jump ahead 15 years or so to today, and this is great news for me and other serious writers, because now we can get a Neo (used, of course) for under $50 with shipping.

I ordered a Neo2 from a reseller on Ebay, or what I thought was one device, because when the package arrived there were two Neo2’s inside. And now that I’ve been using the Neo2 for a couple months, I’m glad I have a second one. Why? Well, this little device is officially my “forever” word processor. I can type all of my words into this little unit, and as long as I can continue to plug a USB cord into a computer, I’ll be able to transfer my words from the Neo2 to MS Word (or another program).

The genius of this device is its simplicity. It’s basically just a full-size keyboard with a tiny LCD screen. You type your words in, and they’re instantly saved in the memory. From the time you press the “on” button, it’s only about three seconds before the word processing document you were working on last opens up, with the cursor patiently awaiting your next words. The LCD screen shows between three and six lines of text; I’ve found that four lines is perfect for me. It’s powered by 3 AA batteries, so you don’t need an electrical outlet, and the batteries last for hundreds of hours. There’s no internet connectivity, so you’re never distracted by email or web surfing (which you might justify as “research for the book”).

The Neo has a word count feature, so you can know when you’ve met your daily quota and go drinking (or, in my case, since I no longer drink, go swimming, play golf, ski, or climb a mountain). It has a built-in thesaurus, but it’s primitive; the few times I’ve tried to use it, the poor little thing hasn’t understood the word I was trying to find synonyms for; you’re better off sticking with a paperback dictionary and thesaurus. Finally, when you’ve finished a piece and want to put it on your computer to edit, lay out, or publish it, all you do is plug it into the computer’s USB port, and the Neo acts like a keyboard, “typing” your words into the computer at about 200 words per minute, or, for those of us old enough to remember, at the speed of a really fast computer modem. (Whenever I see the words unfurl across the screen, it pleasantly reminds me of my youth, with computers and BBSes.)

I love this device, but I’m not going to do a review of all of its features here. Check out this video or this one, and contact Joe Van Cleave or Cheyanne with your questions. I think it’s wonderful that they’ve found the time to create videos about their Neos; unfortunately, I’m too busy writing.

As far as technology goes that will enable you to simply get the words written, the Alphasmart Neo or Neo2 is the novelist’s missing link.

Eventually, I plan on painting one of my Neo 2’s—probably a hot red like the one above.

Interlude: A Couple of Writing Secrets

Here’s a secret about writing professionally that very few novice writers (and even some professionals) seem to know:

Book-writing is as much an endeavor of numbers as it is one of words. The consistent, daily production of a minimum number of words is the key to getting books written. For novices this minimum word count should be higher, not lower, because writing is one of those few enterprises that, paradoxically, gets tougher as you go on. It gets tougher because—if you’ve been challenging yourself and studying—you, the writer, get better and better. Whereas you once only had one or two tools in your writing toolkit to help you express an idea, when you’ve been doing it for decades, you’re carrying around a toolkit with two dozen ways of expressing that same idea. And as you get better, you also continuously raise your standards, which makes the writing more difficult as well.

One reason why the consistent, daily minimum word count is essential is this: Words add up faster than you think. To aspiring writers, or to people who wistfully declare they’d one day like to write a book, I’ve always given this example: If you were to write just one, double-spaced page per day (about 250 words on average), every day, at the end of a year you’d have the first draft of a novel. Or, if you have a minimum word count of, say, 1,000 words a day, figuring a rest or Sabbath day once a week, that’s 6,000 words a week, or about 25,000 words per month, or the first draft of a respectable-sized novel every three months.

For a long time my absolute daily minimum was 1,000 words, but I upped it to 1,500 last year while writing “the Big Book.” I have days, like all writers do, when producing those 1,000 words is back-breaking mental drudgery, when I regret my decision to become a writer, but fortunately those days are maybe one in a hundred. However, most days—especially if I’m not being distracted by politics, news, social media or the interwebs—I can write 2,000–3,000 words in a five-hour session.

For myself I’ve discovered that, while seemingly indefatigable, I, too, get tired, and my writing endurance has its limits. When producing new work, 7 or 8 hours of writing is the max (this includes 2 hours of early-morning writing and five or six hours in the late morning and early afternoon); for editing or entering revisions into the computer, I can go for 11 or 12 hours, but at great cost to my well-being for the rest of the week.

One final secret. Here’s another reason why a consistent, daily minimum word count is essential: The best way to ensure eventual quality of work is to produce a great quantity of it. I write the first drafts of at least two, often three, books a year. Then, after letting the books sit in a drawer or the closet for some time, when I take them out again to revise them, I have a large quantity of work that I can cut, pare down, condense, and refine. I liken this process to the “sugaring” process.

When I was a boy, each early spring I would help my great Uncle Holland make maple syrup, carrying the two-gallon buckets of sap from the maple trees to where he was boiling it down into syrup. I forget what the exact ratio was, but it took something like 10 gallons of sap to make one quart of syrup. Regarding writing, the point is this: You don’t get the good stuff—the delicious maple syrup—without a hell of a lot of sap.

The Final Steps

Okay, so back to my process. To review, I’ve done the following:

- Written the first draft in longhand or on a typewriter

- Stored the completed draft in a drawer for days, weeks, months or years

- Edited the hand- or type-written manuscript with a blue pen

- Retyped the manuscript into a word processor

- Uploaded the manuscript into Microsoft Word

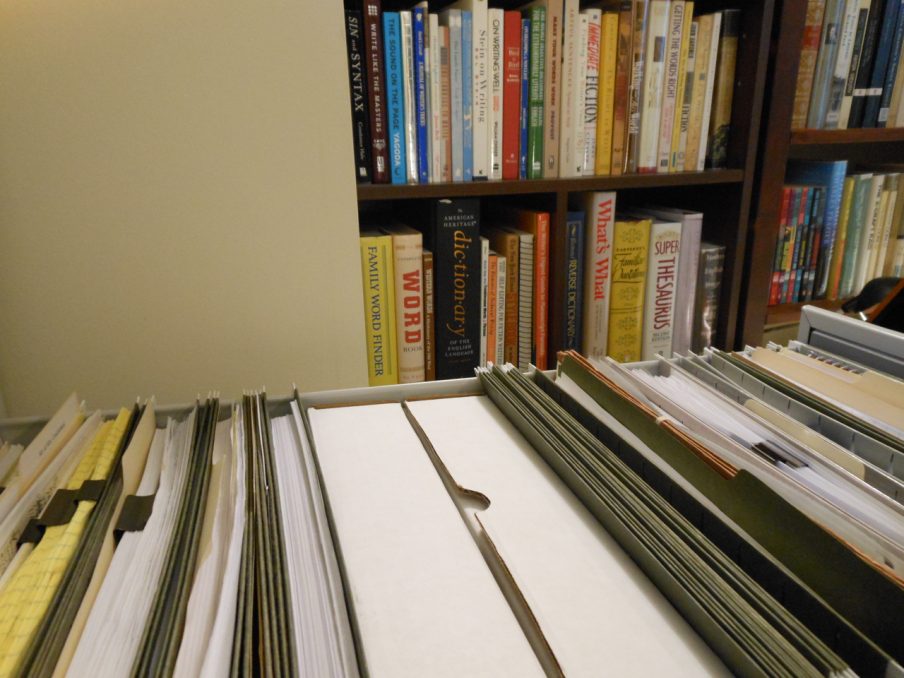

Once the book is in Microsoft Word, this is when I format the text in a nice, readable font (for reading on paper, I choose a good “book style” serif font: Janson, Goudy Old Style, or Hoefler Text). I give the manuscript very large margins (like 1.5 or 2 inches) and use double-spacing to make plenty of room for blue pen work later on. I then print out two copies (storing one in a drawer and the other in the trunk of my car) and back up the file in at least three places. And then I forget the book for a while and write the first draft of something new.

When I return to the printed-out book, I do my blue-pen work on it, then type in the changes and print out the revised draft. Each time I create a new draft, I change the title of the MS Word file, so it reads as “New_Novel_X_Draft_MMDDYY.” Every day while I’m entering the blue pen revisions, I do a “Save as…” and change the date on the file name to that day’s date. This ensures that, in the worst case scenario, I’ll only ever lose one day’s writing, or, if I accidentally delete a passage, I can go back to a file from a couple days earlier and recover the passage.

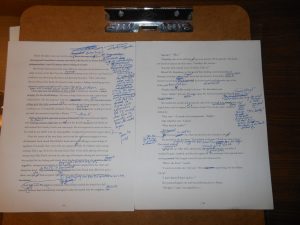

I do this blue pen work and enter the changes into MS Word 3–5 more times, depending on what it takes to, as Hemingway put it, “get the words right.” Each time I print out a fresh copy, I read sections aloud to iron out any kinks in the sentences. Finally, the book is ready for others to read it. I print out copies of the penultimate draft for my couple of test readers, send it to them with clear direction on what I’m asking them to read for, and wait.

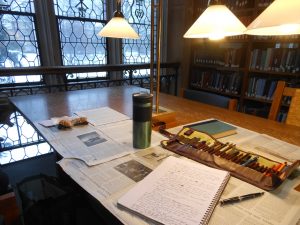

In any given week, I’m working on as many as three different projects, each at a different stage in the process, rotating through them throughout the day. Early in the mornings (around 4:30 a.m.) is reserved for the first draft of my newest work or a project that requires me to remain in a semi-dream state in order to put myself there and write about it. For example, right now I’m working on a novel about a Biblical hero, where I want every sentence to be a gem; this requires total quiet and no distractions—just me and the pencil, or me and one of my typewriters. Later in the morning, I formally “go to work” and set up in one of my usual spots in Vassar College’s beautiful Thompson Memorial Library. This is where I continue writing the new thing, or type in the first draft pages from a few days earlier into the Neo2.

Then, in the afternoon, I do my blue pen work on a different project. Currently that project is a new Dakota novel—a prequel to the series—which I hope to release by June. Sometimes I’ll stay in the library or at home to do the blue-pen work, but more often than not I put the pages on a giant artist’s sketch board and work on them in my car, parked by the Hudson River, or, if it’s a pleasant day I’ll go to a park (Bennett in Millbrook, Poet’s Walk in Rhinebeck, The Morse Estate in Poughkeepsie) and do the blue-pen work there.

Notice that I put some distance of time during the day between the creative work (first draft) and the editorial work (later drafts). This is to prevent my internal censor or editor from rearing its critical head early in the morning, a phenomenon that invariably puts the kibosh on any creative flow that might be trying to happen. I find I’m able to placate my internal editor by telling it, “Don’t worry, Marvin [my editor’s name]…you’ll get to do your editing stuff this afternoon. And you’ll also get to edit what I’m writing now, but not for a long while.”

Convoluted But Magically Productive

Is my writing process, where I put off using the computer as long as possible, convoluted? Yes, I have to admit, it is. But it’s also been miraculously productive. I’ve been using this process, or a variation of it, for almost 30 years.

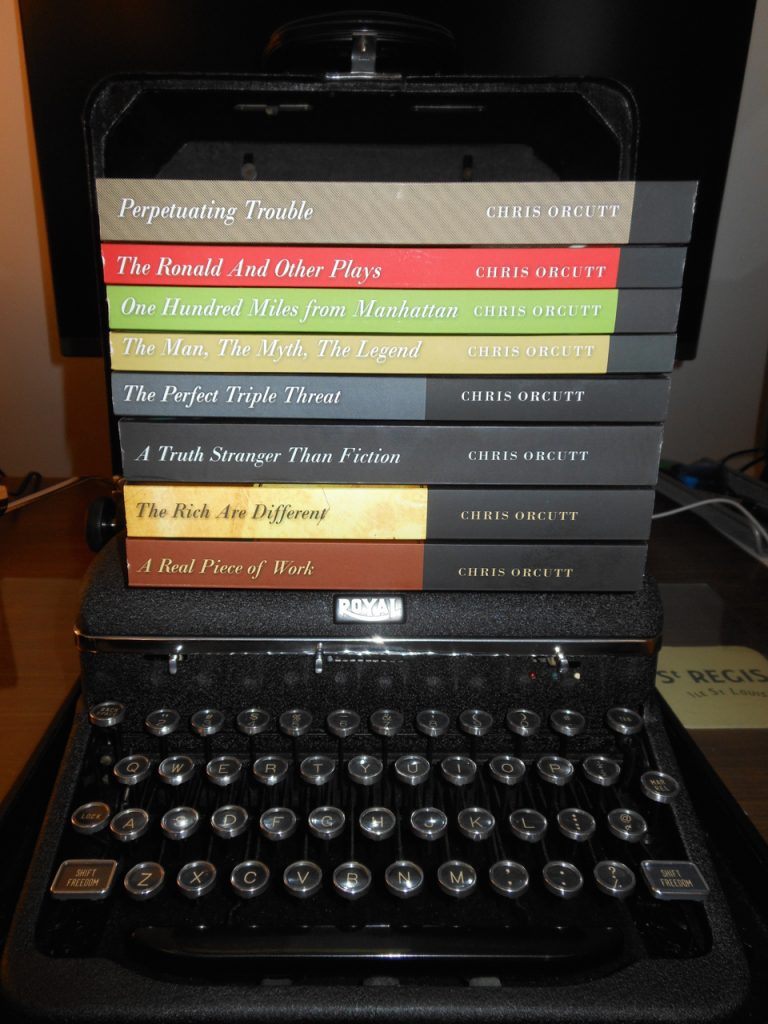

Since late 2012, when I published the first Dakota Stevens mystery, A Real Piece of Work, I’ve put out eight books. Eight books in 5 years, or an average of one book every 7½ months. And not eight anemic, hothouse-grown 30K-word “books” that certain so-called writers turn out every six weeks. The process I use ensures that my efforts are consistently directed towards quality, and the professional reviews I’ve received have proved my process works for me.

All right, now that I’ve gone into great detail about my low-tech writing process, let me briefly describe what I see as its greatest benefits. One, by writing using a variety of tools and media (from pen, pencil or typewriter, to blue pen, to word processor, to computer), you get to see your words in a number of different formats: on paper, computer screen, etc. Two, using low-tech writing methods, especially for the early drafts, ensures that you can create with a minimum of distraction. And three, by hand-writing or typing your words, hand-editing the pages, and retyping them, you are interacting with your words over and over again, constantly honing and refining them.

The Way Doesn’t Exist

So there you have it: my low-tech writing process. I should emphasize, however, that this is my process, developed over three decades. If you’re a young or aspiring writer, you’ll want to try your own process for a while. Get some experience doing things the “high-tech” way, and then, when you learn that faster isn’t necessarily better or more efficient (and it certainly isn’t less distracting), come over to the low-tech process.

Over three decades, I’ve seen a hell of a lot of writing-related software programs, tools, reference materials, websites and “apps” come and go, and the two latest that I predict will go the way of the dodo within a few years are the Freewrite “smart typewriter” and the online “app” Grammarly.

(By the way, a message to the folks at Grammarly: Please stop preempting my YouTube videos with your obnoxious ads. I wish you clowns would disappear already; all you’re doing is making people dumber by absolving them of the responsibility of learning that “pesky grammar stuff.”)

As my super-tech-savvy friend Jason Scott likes to Tweet of certain inane products, companies or emerging technologies, Freewrite and Grammarly are, in my opinion, “DOOMED.” I give them both two years, tops.

The bottom line is, while some writers will spend their time arguing for all of these allegedly convenient, “time saving” tools, apps, and such, and others will spend a lot of their time holding out against the advance of technology, serious writers like me are going to find a process that works for them, stick with it, and simply keep producing books.

The philosopher Nietzsche once wrote,

“This is my way. What is your way? The way doesn’t exist.”

Comments (0)