To All So-Called Authors: Stop Doing This; You Look Like Idiots

Maybe I shouldn’t be giving away my writing secrets.

Maybe I should be like Ernest Hemingway, who, with the exception of a couple of Paris Review interviews in which he gave cryptic answers to questions about writing craft, was selfish with his knowledge throughout his life and shared very little of it.

But there’s something that I’m seeing over and over and over again in so many novels published today that I have to say something. In both genre and mainstream novels, whether indie- or traditionally-published, I see “very good” or even “great” modern authors making the same mistake. Incredibly, one such book on Amazon has over 1,000 4- and 5‑star reviews.

This trend has reached a point where someone has to say something.

And as one writer who knows what he’s doing, I am happy to take on this cause célèbre.

Here’s the deal: When you write a sentence, one of the things you have to decide is which part of the sentence is going to get the most detail or emphasis—the subject, the verb, or the object (the receiver of the action). Each of these units is called a syntactic slot. The subject is the person or thing performing the action. The verb is the action. And the object is the person or thing receiving the action. The general rule of thumb is that you don’t pack all of your syntactic slots. Packing slots creates cluttered, distracting sentences with hazy images that give the reader very little to latch onto.

(Of course the above is highly simplified—explained exactly as I did when I taught writing at Baruch College, City University of New York. I received a Distinguished Teaching Award for my efforts.)

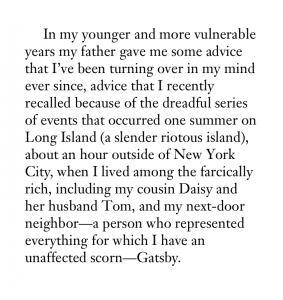

Let me give you an example of a bad sentence—one that violates the above rule of “don’t pack all of your syntactic slots.” Following is the sort of opening sentence often found in poorly written fiction (especially poorly written genre novels):

When the lone stoplight in Hudsonville, Texas—a dry, dusty West Texas town, population 1,400—turned green, Blake Tanner, Dallas private detective, took a drag on his hand-rolled cigarette, flicked the stub into the wind, glanced at his piercing blue eyes and devil-may-care jet black hair in the rear-view mirror, and slammed his hand-tooled cowboy boot on the accelerator of his rebuilt, sky-blue 1963 Cadillac convertible with the 400hp V8, reveling in the khaki cloud of dust he left behind the car and looking forward to hunting down his quarry, bank robber Hal Driver, somewhere in the next lonely, dusty, desperate town.

Now…obviously I’ve been hyperbolic with my example; most opening sentences (even those of poorly written novels) are not that long or ponderous. But even novels with openings composed of several shorter sentences are often laden down with packed syntactic slots—attempts by authors to pile up the information.

Why, oh why, do writers (actually, more often, authors) do this?

There are several reasons:

1. The author isn’t a very good writer. He read somewhere that good fiction is about detail (which is partly true), so he makes a point of packing every single clause and syntactic slot full of detail.

2. The author is lazy, so she either doesn’t write multiple drafts of her work, or she doesn’t take the time in later drafts to edit out the unnecessary details. She wants to get it “all in there,” but isn’t willing to do the heavy lifting, which is to keep in the story only those details that are truly important. A story isn’t every thing that happens; it’s every important thing that happens.

3. The author doesn’t trust in the reader’s intelligence, probably because he isn’t particularly intelligent himself. He believes that he needs to spell out every single thing for the reader because the reader, in his opinion, is a dip-shit incapable of forming a mental picture of a scene unless provided with ALL of the details. For example, in a recent very highly-rated mystery novel, the author describes the counter at a DMV office as being “chest-high.” We’ve all been to DMV offices, and guess what? The counters at all DMV offices are chest-high.

4. The author doesn’t trust in the reader’s patience. She doesn’t believe that the reader will continue to read beyond the first few sentences or paragraphs, so she puts in every detail that she thinks will hook the reader and make him want to read on. What she doesn’t understand is this: The way to keep readers reading is by withholding information, not by dishing it out. Put another way, don’t take the reader where he wants to go.

Whether you’re a relatively new writer trying to finish your first novel, or you’re a seasoned author putting the finishing touches on your latest work, I hope you’ll take into account what I’ve written here. Nothing makes a potentially good story look more amateurish than packed syntactic slots or cluttered sentences, so no matter what stage you’re at, I strongly recommend you go back to the writing table and address this aspect of your work.

Comments (2)