A Shattered Paradigm

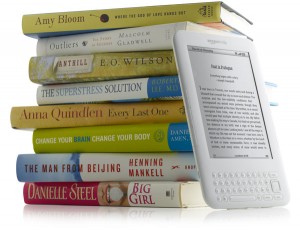

I have read hundreds of books on writing. Conservatively figuring an average of 15 per year, over 24 years that makes 360 books on the subject. Books on voice, style, grammar, plotting, dialogue, point of view, syntax, narration, description, characterization, novel writing, technical writing, short story writing, nonfiction writing, query writing, getting an agent and getting published. But, none about what it means to be your own publisher. And none specifically about how to go forward as a writer during this time of the rise of e‑publishing and the slow, inexorable decline of print publishing.

I often go to my bookcases for tried-and-true books on aspects of writing I’m having problems with, but for help on this issue, like Old Mother Hubbard I’ve found the cupboards bare. Even the few books about marketing can’t help me. Less than 2 years old, they’re already woefully out of date.

The trouble is, the paradigm I’ve been laboring under for 20-odd years is now shattered, and I’ve been trying in vain to salvage some of the pieces. It’s as though I’ve dropped a family heirloom vase and am in denial about its shattered state.

The trouble is, the paradigm I’ve been laboring under for 20-odd years is now shattered, and I’ve been trying in vain to salvage some of the pieces. It’s as though I’ve dropped a family heirloom vase and am in denial about its shattered state.

Ye Olde Publishing Paradigm (the one that ruled for centuries):

Writer learns craft, maybe works at a newspaper for a while, gets a few short stories published. Writes a novel, perhaps a few, and gets an agent. Agent contacts the major publishers, sells the book (taking 15% in the process). Author gets an advance against royalties (a loan, not free money). Publisher negotiates rights of first refusal on author’s next two books, publishes the first book 18 months later, hopefully in prestigious hardcover. Then trade paper, then mass-market (pocket-sized) paperback. If the author is lucky, someone from Hollywood contacts his agent to option (not buy) the book for a film that, chances are, will never get made. In the meantime the book has hopefully made its way into bookstores, where readers are hopefully buying it and loving it. There may be other subsidiary steps I missed but this is the general idea:

Writer –> Agent –> Publisher –> Bookstore –> Reader

The 21st Century Publishing Paradigm: The writer is the publisher. She writes what she wants to write, and when she publishes it, it goes directly to readers for their purchase and enjoyment. There are no gatekeepers like agents and traditional publishers preventing the writer from reaching readers directly. In fact, the only intermediary is the company that owns the delivery system, or bookstore—Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing, B&N’s Nook, Smashwords, iBooks, etc.

Writer –> Bookstore –> Reader

In case you missed it, in the New Paradigm two large and obstinate obstructions between the writer and the reader have been removed.

As I said in my article of a few weeks ago about why I’m publishing my mystery series on Kindle, and as I said to half a dozen newspapers during my self-made publicity “junket,” a writer writes to be read, not to be forced to jump through hoops and told that the market won’t like what the writer is writing. My response to that old chestnut is one of the most basic principles of free market economics: let the market decide what it likes.

When I look at my shelves of hardcover fiction, I feel a pang of sadness for something that will probably never be: my own writing in prestigious hardcover, with acid-free paper, an eye-catching cover and the logo of a major publisher on the spine. Even worse, nowadays when I look at these once proud volumes (the pinnacle of book technology), it’s as though I’m seeing living fossils. I know something important without a lot of evidence for it: The vast majority of print books are going to fade away, to be replaced by slimmer, sharper, more powerful tablets.

When I look at my shelves of hardcover fiction, I feel a pang of sadness for something that will probably never be: my own writing in prestigious hardcover, with acid-free paper, an eye-catching cover and the logo of a major publisher on the spine. Even worse, nowadays when I look at these once proud volumes (the pinnacle of book technology), it’s as though I’m seeing living fossils. I know something important without a lot of evidence for it: The vast majority of print books are going to fade away, to be replaced by slimmer, sharper, more powerful tablets.

One piece of evidence I have for this is that there are successful, traditionally published authors out there who have switched to self-publishing exclusively. In his thorough primer on electronic self-publishing, Let’s Get Digital, David Gaughran profiles an author named Bob Mayer, whose last three book deals prior to self-publishing totaled over a million dollars. Yet, Mayer walked away from traditional publishing and now self-publishes his work. “The main difference,” Mayer says, “is that I have more control than I ever did in traditional publishing.”

My point is, when commercially successful writers like Bob Mayer are leaving traditional publishing behind, how long will it be before the Stephen Kings and Tom Clancys of the world begin to leave it as well?

We’re witnessing a rare occurrence—an overlap in evolution, like when Neanderthal man existed on the planet at the same time as Homo sapiens. Neanderthal man was stronger and probably should have survived, but Homo sapiens was smarter, and did.

So, what is a writer to do who has operated under the old paradigm for all of his adult life? Suddenly, with no gatekeepers in his way, he can publish (from the Latin publicare - to announce, to make public)  anything he wants, anytime he wants, reaching readers directly while reaping the lion’s share of the profits. This being the case, should he continue to pursue mainstream publication or representation? If so, why? For prestige? To fill a need for outside approval? Assuming one’s writing is of quality, how is print publication any better—any more prestigious or virtuous—than e‑publishing? Are the words of The Great Gatsby any less poetic and utterly perfect presented in e‑ink than they are in print? No. In fact, I submit that you could paint those words on a dark cave wall and they would still be as great. Great writing is great writing, regardless of the medium in which it’s published or who decided to publish it.

anything he wants, anytime he wants, reaching readers directly while reaping the lion’s share of the profits. This being the case, should he continue to pursue mainstream publication or representation? If so, why? For prestige? To fill a need for outside approval? Assuming one’s writing is of quality, how is print publication any better—any more prestigious or virtuous—than e‑publishing? Are the words of The Great Gatsby any less poetic and utterly perfect presented in e‑ink than they are in print? No. In fact, I submit that you could paint those words on a dark cave wall and they would still be as great. Great writing is great writing, regardless of the medium in which it’s published or who decided to publish it.

One of the key tenets of the old publishing paradigm was that as gatekeepers, agents and editors ensured that only good quality writing reached readers. Writing that didn’t meet certain standards was rejected. Whether or not their role as gatekeepers has been of service to readers is debatable; but what isn’t debatable is the idea that readers deserve material that is well written. And with writers now filling the roles of agent and publisher for our work (or really publisher and publicist), it behooves all of us only to publish the best writing we can write.

We all need to become our own best editors, too, learning the rules and craft of writing inside-out so that our work is indistinguishable in quality from any work published by “professional,” traditional publishers. Doing this en masse is the only way to defeat the hackneyed argument by the publishing establishment that self-published work is inferior in quality. Doing this will raise the overall quality, benefiting all writers and, more importantly, our readers.

One of the reasons I wrote this piece was to think this issue through for myself, because like a lot of writers who labored under the old paradigm, I’m now unsure about how I should proceed. Everything has changed. But one thing that hasn’t changed is the writing itself. The writing is going to be good or bad, and will come easily or with difficulty, no matter how it is published. However, now that the barriers to readers have been removed, we writers don’t have the publishing industry as a scapegoat anymore. The only limitation on how much we publish, and its quality, is ourselves.

So, as for myself, I know what I have to do, and it’s the same thing I’ve done every day in one form or another, and that’s just write. Write the best I can, every day, and then decide what’s worth publishing.

Comments (2)