Backstory: The Story Behind the Second Dakota Stevens mystery, The Rich Are Different — Part 2

Last week, in Part 1 of the story behind The Rich Are Different, I described my experiences during 9/11 in Manhattan and the months following, and how they pushed me to quit my corporate job and focus on being a novelist full-time.

Now, in Part 2, I’m going to describe the development of the novel that rose from the ashes of 9/11: The Rich Are Different.

The Mutant Alien Version of The Rich Are Different

The novel I wrote on my IBM Selectric at the White Plains Merrill Lynch office, and in longhand on the train to and from the office, was about Montana.

Ever since I was a boy, I had wanted to go to Montana and see Yellowstone National Park, the National Bison Range, and Glacier National Park. I’d been a Boy Scout in my youth and I missed the outdoors. Plain and simple, I was sick of New York City and needed the kind of restoration that only grand, magnificent open spaces could give me, spaces like Montana—“Big Sky Country.”

So I wrote a novel about a painter, an artist from New York City, who goes to Montana after 9/11 to restore his artistic soul. While there, he meets a beautiful woman park ranger. The two fall in love; she visits him in Manhattan, decides there’s no way she’s moving there; and so he abandons his life in New York to join her in the wilds of Montana. However, as he’s driving across the country with all of his possessions and his dog, he finds out there’s a massive forest fire in the park where the woman is a ranger, and soon thereafter her remote station is discovered in ashes.

The End.

Now, why did I go into all of that detail last week about the months preceding the writing of The Rich Are Different, and why did I describe the plot of the novel’s first draft? Because I want you to see that novel-writing is messy; that we novelists, even if we have a semblance of an outline to follow, usually don’t know exactly where we’re going with a story. The most important thing about the first draft of a novel is not that it’s perfect, but that it gets written.

Now, why did I go into all of that detail last week about the months preceding the writing of The Rich Are Different, and why did I describe the plot of the novel’s first draft? Because I want you to see that novel-writing is messy; that we novelists, even if we have a semblance of an outline to follow, usually don’t know exactly where we’re going with a story. The most important thing about the first draft of a novel is not that it’s perfect, but that it gets written.

One of the most apt metaphors for novel-writing was given by novelist E.L. Doctorow, who said that writing a novel was like driving a car across the country, but only traveling at night: You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the entire trip that way. Based on what I’ve learned about this work, I would add the following to his metaphor: You simply have to have faith that, if you keep putting one sentence after another, you’ll eventually reach your destination: a finished draft of a novel.

I spoke of the months preceding the writing of The Rich Are Different, and then I mentioned the writing of the Montana novel, because I wanted you to see that the final Dakota Stevens mystery novel resulted from an iterative process.

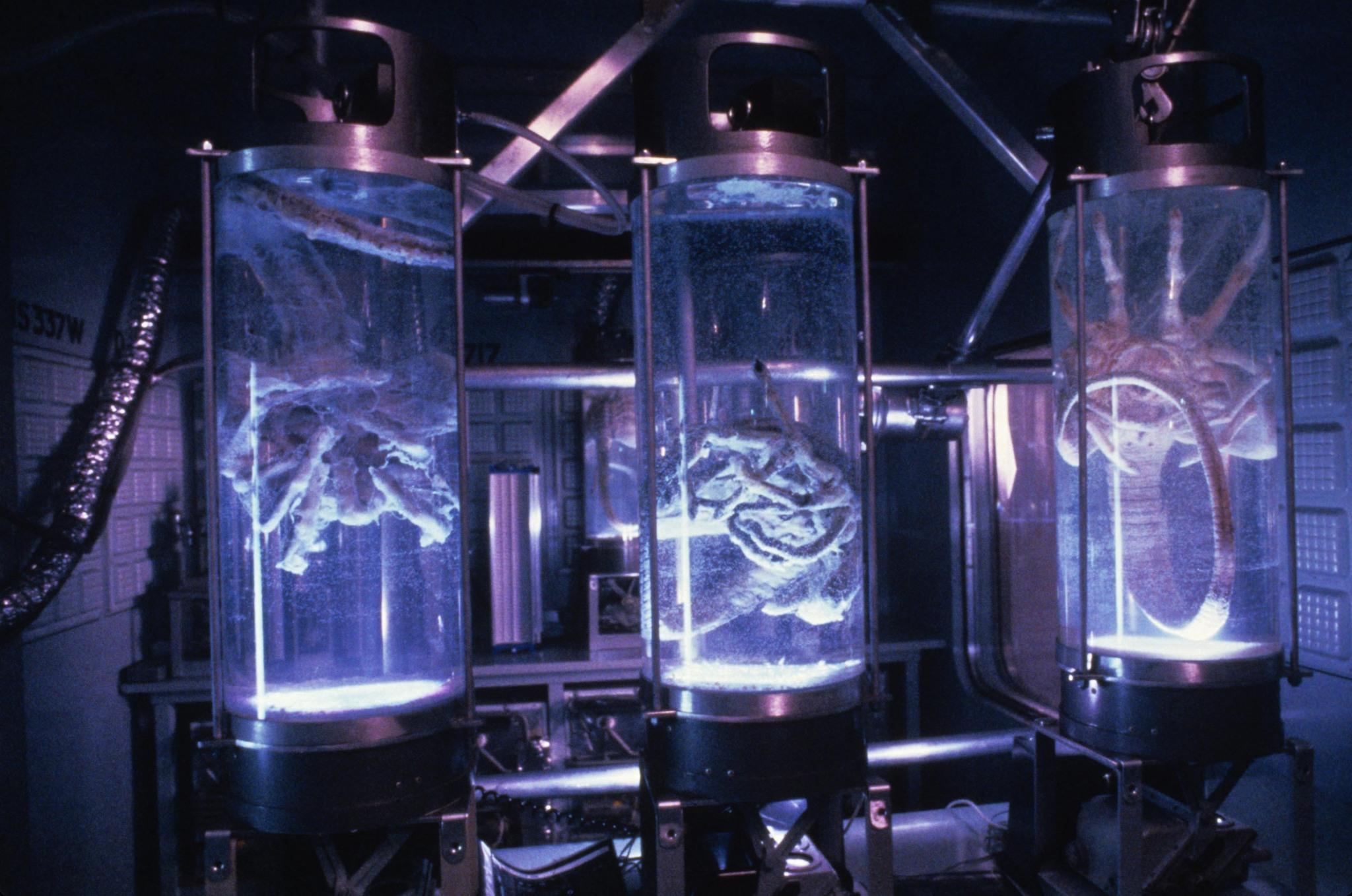

In one of my favorite movies, Aliens directed by James Cameron, there’s a scene in which Ellen Ripley and the surviving Colonial Marines find a lab with dozens of mutated aliens in glass tanks.

In one of my favorite movies, Aliens directed by James Cameron, there’s a scene in which Ellen Ripley and the surviving Colonial Marines find a lab with dozens of mutated aliens in glass tanks.

Here’s the corollary when it comes to writing: For every shiny, riveting, smooth-reading, page-turning, finished novel that readers buy and enjoy, the novelist likely produces five or six of those mutant aliens that will be forever trapped behind glass.

A Boyhood Dream Fulfilled: Montana & Yellowstone

So, I wrote what I referred to as my “Montana novel.” Then, for most of May 2002, I went out to Montana, rented a car and drove 3,000 miles—all through Montana, seeing Yellowstone, Glacier and the National Bison Range; and through Wyoming and Idaho. I camped out, hiked, and, in the evenings, bought drinks for the natives at whatever remote roadhouse I ended up.

One night, in a dive outside of Virginia City, Montana, I met a group of Native Americans. It turned out they were ranch hands, most of them, and I asked them how the then-recent reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone had affected ranches in the area.

The leader of the group, a classically good-looking Native American with long, shimmering dark hair, turned to me in his barstool and said, “Wolves don’t bother us none. See, ’round here, we got the three S’s.”

“Three S’s?” I said.

“Shoot, shovel and shut up,” he said.

I laughed, and all his buddies laughed, and I bought them another round. In fact, I bought those guys so many rounds of drinks that they promised if I stuck around, the next evening they’d induct me into their tribe and give me an Indian name. Alas, I had reservations at Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone the next afternoon, so I had to leave that night, but I always wondered what name they might have given me.

This experience with the Native Americans made a deep impression on me, and a couple of years later, when I transformed the Montana novel into what became the mystery The Rich Are Different, I made a neighboring Indian tribe one of the groups of suspects.

After leaving Virginia City, I went to Yellowstone and stayed there for a week, in the hotels or at campgrounds. Later on, when I wrote the mystery novel, I had Dakota and Svetlana follow one of the suspects (beautiful blonde Heather Van Every, my homage to Hanna Van Hastings) to Yellowstone, where they stayed at the Old Faithful Inn. My descriptions in The Rich Are Different of the Old Faithful geyser, the inn interior, the herd of elk on the grass in front of the park administration building, the sleepy town of Gardiner, Montana bordering the north side of the park—all of it came from that visit to Yellowstone.

But even before I got to Yellowstone, I had been musing about the makings of a mystery novel while touring ghost towns throughout Montana. And the second I walked down the main drag of one of them—Bannack, Montana, once a prosperous silver town—and I saw the old saloon, the jail, the hotel, several storefronts and, up on a hill overlooking the town, a gallows and a boot hill graveyard, I asked myself, “What if some eccentric rich person created a mock Old West town, populated it with actors, and people could go there for vacations to escape the rigors of modern life? What if the place had its own railroad, and it was a time portal back into 1885? What if there was no electricity, one telephone, et cetera? And what if the rich owner of the place died under mysterious circumstances and a private detective from the East was called in to investigate?”

But even before I got to Yellowstone, I had been musing about the makings of a mystery novel while touring ghost towns throughout Montana. And the second I walked down the main drag of one of them—Bannack, Montana, once a prosperous silver town—and I saw the old saloon, the jail, the hotel, several storefronts and, up on a hill overlooking the town, a gallows and a boot hill graveyard, I asked myself, “What if some eccentric rich person created a mock Old West town, populated it with actors, and people could go there for vacations to escape the rigors of modern life? What if the place had its own railroad, and it was a time portal back into 1885? What if there was no electricity, one telephone, et cetera? And what if the rich owner of the place died under mysterious circumstances and a private detective from the East was called in to investigate?”

At this point I didn’t know that I would start writing a mystery series. I didn’t even have a name for my would-be detective. All I had were some interesting settings for a mystery.

Gatsby Meets “The Man with No Name”

When I returned to New York, I typed up my hours of audio notes dictated to tape recorder while driving through Montana, and then I forgot about the idea for over a year.

Under the terms of my severance agreement, I was continuing to receive my full salary for a year (along with unemployment insurance; Lou, himself recently liberated from Merrill, referred to this state of financial grace as “the double-dip”).

But I wasn’t ready to be a full-time novelist every day, all day long—yet. I took a job as an adjunct lecturer at Baruch College, teaching Freshman Composition, Introduction to Literature and Business Writing courses. I had discovered what I called “Yeti” because its rarity had made others question its very existence—the elusive “triple-dip”: full salary from old job, unemployment insurance, and some income from a part-time job.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the backstory behind the first novel in the Dakota series, A Real Piece of Work (ARPoW), and how I began writing that book early in 2003. Well, by the summer of 2003, finished with the first draft of ARPoW, I pulled out the old “Montana novel” and my Montana trip notes and launched immediately into the novel that became The Rich Are Different.

Early on in the writing of it, I decided I wanted to pay homage to two works I deeply admired: movie Westerns, of which I was an avid aficionado, and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece The Great Gatsby. I wanted the first part of the novel to evoke Gatsby, with its Long Island North Shore locales and its refined, elegant sentences; and I wanted the second half of the novel, which took place largely in Montana, to evoke classic westerns I admired.

I constructed the case such that Dakota and Svetlana are hired by the sister of the killed resort owner, and they eventually have to go undercover in the mock Old West town.

A bit of Hanna Van Hastings lives on in the book, through the attractive blonde suspect Heather Van Every. The Native Americans I drank with in Montana appear as suspects, too. The Montana setting plays a major role in the novel, and I was pleased to hear from a couple Dakota readers—Montana natives—a few years ago, who told me I’d perfectly captured the Montana zeitgeist. I was confident I had, but ever since I was a newspaper reporter, I’ve prided myself on “getting it right”: making readers with inside knowledge of a place or a profession nod and smile to themselves in the middle of reading.

The Rich Are Different is, in my opinion, a much more intricate work than the first novel in the series, A Real Piece of Work. The way I’ve described the difference between the two books to readers and aspiring mystery writers is this: In ARPoW, Dakota and Svetlana follow a trail of bread crumbs through a perilous, enchanted forest; in TRAD, they have to navigate an intricate 3D spider web.

The Rich Are Different is, in my opinion, a much more intricate work than the first novel in the series, A Real Piece of Work. The way I’ve described the difference between the two books to readers and aspiring mystery writers is this: In ARPoW, Dakota and Svetlana follow a trail of bread crumbs through a perilous, enchanted forest; in TRAD, they have to navigate an intricate 3D spider web.

Well, that concludes the backstory of The Rich Are Different.

And in a few weeks, I’ll write about the backstory of the longest Dakota mystery thus far, A Truth Stranger Than Fiction.

Comments (0)