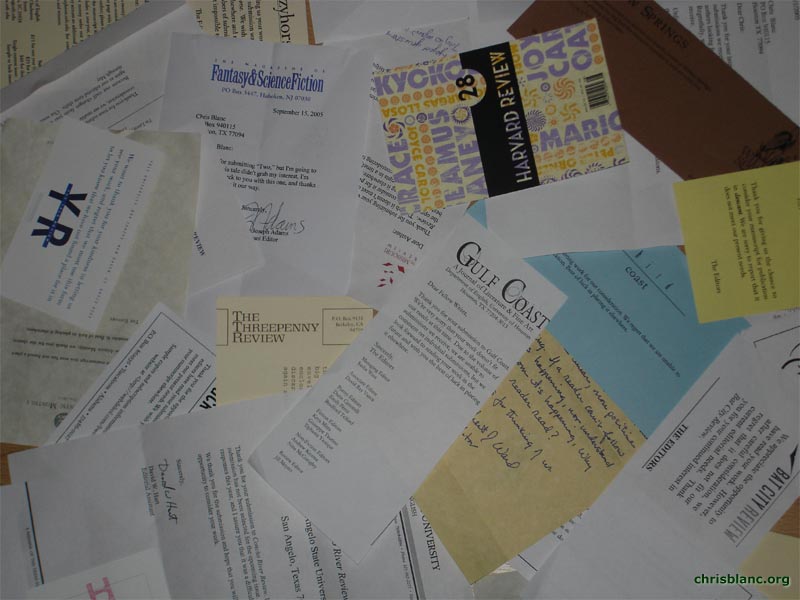

"Rejection": A collage by Chris Blanc.

"Rejection": A collage by Chris Blanc.

Crossing the Rubicon: Replying to a Rejection from a Literary Journal

In the literary world, what I did is tantamount to crossing the Rubicon. It’s something that, in 20 years of submitting my work to literary journals, I have never done before:

I replied to a rejection letter.

Actually, I replied to a rejection email (times have changed), but the substance of the transaction was the same: instead of shrugging off the rejection as I’ve done hundreds and hundreds of times before, this time I decided, “Hell, they’re rejecting my work anyway, so I might as well point out their disrespectful behavior.”

How is this crossing the Rubicon, you ask? Well, everything I’ve read about the writer–publication relationship has been explicit: Never send an angry or contentious reply to editors, because it only makes you, the writer, look bad. The other problem is, I don’t know if the editors of these literary journals talk with each other, and whether I might be blacklisted because of my action:

“Rejection”: A collage by Chris Blanc.

“Oh, here’s a submission from that Chris Orcutt. I’ve heard about him—he’s that troublemaker, that writer who sends nasty replies to rejections. We don’t need to read this. Send him a form slip.”

Let me give you some backstory here. The rejection email went to an account that I set up solely for story submissions, and I hadn’t checked the account in a while. And the reason I hadn’t checked it is this: I had stopped submitting stories—probably a year ago—because (I’ll admit it, I’m human) I got tired of being rejected.

Over the past three years, I wrote 39 stories and made over 250 submissions, all without a single acceptance. Anywhere.

Interestingly, these are some of the same stories that readers of The Man, The Myth, The Legend are now calling “brilliant,” “deliciously cheeky and ironic,” and “beautiful use of our language.”

But back to my submissions over the past three years.

During that time, because of the quality of the stories I was submitting, I did manage to establish a correspondence with major magazine editors—including the accomplished, venerable and gracious C. Michael Curtis at The Atlantic—and all of them, even though they were rejecting my work, always treated me with respect.

The Atlantic, The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Missouri Review, Mid-American Review—they’re class acts, every one of them.

I can’t say the same of the literary journal I replied to this morning. I won’t mention it by name, but I will say that it used to be considered a prestigious fiction journal, and it still publishes quite a few name authors.

So why did I reply to this particular rejection, when I’ve never done it before? Read it for yourself, and I think my reasons will be obvious:

Dear Contributor:

Thank you very much for submitting your work. After careful consideration, the editors were not able to accept it for publication.

We would like to offer personalized letters or feedback but limitations of time and staff have made that impossible at the present. We wish you the best of luck in finding a journal to publish your writing. The editorial staff, including the editor-in-chief, ******* *******, welcomes critical response to past issues of the magazine if you wish to include any in future submissions or letters. If you identify yourself as a writer who submitted to ********, you may order back issues at a fifty percent discount.

With best regards,

The Editors

I’ll admit that their insultingly generic salutation of “Dear Contributor” irked me. Not to mention their dubious “careful consideration” of my work. They gave me no indication that my story had been read at all. In fact, every indication is that mine was one of dozens or hundreds of others summarily rejected because the Editors were buried in manuscripts.

And then they had the temerity to intimate that I might actually want to buy something from them? Please.

But what really bothered me—the thing that made me have to reply to them—was the ridiculous length of time that had passed between my sending them the story in question and their rejecting it. (NOTE: In the literary world, a few months is considered an acceptable length of time to wait for a reply.)

Dear “The Editors”:

According to my records, the last story I submitted to you was “The Last Great White Hunter,” and that was on October 1 of last year. Fourteen months ago.

After a YEAR and two months before you could respond to my submission, not only did I completely forget that I submitted anything to you, but I stopped caring. I won’t be submitting anything to you again.

Another point: In the future, if a writer takes the time to send you a well-written story, if that writer shows respect for you and your time by not sending you something that is clearly amateur (e.g., mistakes in grammar and punctuation), if that writer is clearly a professional, then that writer at least deserves a personal response. This is something that the major magazines including The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and Harper’s have done for me and other good writers, so why can’t you? Reserve your “Dear Contributor” salutation for the so-called writers who treat this endeavor as another lottery.

Please do not bother to reply to this email. I wouldn’t want to wait another YEAR and two months before someone responded.

On a personal note, I do wish the Editors and all of the staff at ******** a happy holiday season and a New Year of health and prosperity.

Thank you for your time.

Sincerely,

Chris Orcutt

Once I had written my reply, I sat in my chair with my finger poised over the mouse, and the cursor over the Send button. What I felt was a faint taste of what Caesar probably felt when he stood on the bank of the Rubicon, debating whether to defy the Roman Senate by crossing that insignificant little stream.

Caesar’s crossing committed him to a future course of action, and my pressing the Send button would not only eliminate this particular literary journal as an option for future publication, but possibly many others. Over 20 years of submissions, I had established a reputation (albeit modest) as a writer of professional-quality work, a writer who had taken rejection in stride, and here I was, about to potentially undo all of that with a single email.

I thought about this for several minutes, and then I gradually realized something: I don’t need them anymore. They aren’t the only game in town now. Although publication in them would be nice, I don’t need them to reach readers the way I used to. If literary journals won’t publish my stories in the future, it doesn’t matter; I can publish them myself in ebook format, reach more readers, and make more money on them than I ever could by being published in an obscure, incestual† literary journal that the general reading public doesn’t read anyway.

†See my comment below regarding my use of the non-word “incestual.”

Caesar is said to have quoted a line from a play as he crossed the Rubicon, saying, “Alea iacta est! Let the die be cast!” Just before I hit the Send button on my email, I said aloud one of my own favorite lines about commitment—spoken by King Claudius in my favorite Shakespeare play, Hamlet:

“Do it, England.”

And with a click and an audible whoosh, my message went out.

Do I regret doing it? No. The literary journal in question is only one of many that engage in this kind of disrespectful behavior towards good writers. They forget that they are utterly dependent on writers for their content.

No content, no journal. Period.

I plan to continue to send stories to the above-mentioned better magazines, and, publication or no, I’m hoping they’ll continue to read and be respectful of my work.

And speaking of work, it’s time for me to get back to it.

Postscript: A few days after I made this post, my short story collection The Man, The Myth, The Legend was voted one of the Best Indie Books of 2013. What makes this particularly gratifying is that 9 of the 10 stories in the collection were among the 39 that literary journals had rejected over the past three years.

Pingback: Things Other People Posted | Cuisine of Loneliness

Pingback: Chris Orcutt: The Man Has Guts (as Well as Glory) Part I | Nanotwit