His Pen Was Quick

Mickey Spillane, late in life.

On July 17, Mickey Spillane, creator of the infamous Mike Hammer PI series, died. He was 88, and by all accounts he lived a pretty cool life.

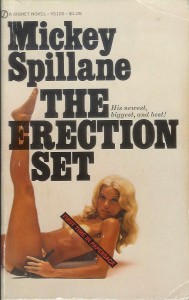

In addition to writing several bestselling novels that readers adored, Spillane played a mystery writer on the 70s TV show Columbo, appeared in several commercials for Miller Lite beer, and married a hot second wife, Sherri Malinou, who posed for the cover of his novel The Erection Set.

There are far better obituaries about Mickey out there, so this entry won’t detail his accomplishments. Rather, I’d like to talk about certain ideas on writing that he espoused (or suggested through his work) and what I learned from him. For lack of a better name, I shall call these the “Spillane Principles.” I believe that all of us aspiring mystery writers can learn a lot from Mr. Spillane.

Ultimately these ideas all come down to the number one ingredient necessary for commercial fiction: narrative drive. The best definition of narrative drive I have found is on the second page of Larry Beinhart’s book How to Write a Mystery (it’s excellent by the way): “Narrative drive is the promise—or threat or tease or suggestion—that something is going to happen.”

Spillane Principle #1: Don’t take the reader where he wants to go.

Time and again in the Mike Hammer novels, when Spillane ends a scene, the scene that follows has nothing to do with what has just transpired. For example, if he closes a scene with Hammer in a lusty embrace with a nude dame, you want him to open the next scene with hot details about the act, or at least some internal monologue by Hammer about what happened. Instead, Spillane puts you in a room with a new corpse and three fat, sweaty detectives.

Another way that Spillane doesn’t take the reader where he wants to go has to do with clues. Hammer finds a bullet, a piece of evidence the cops miss. We want Hammer to start following this new line of inquiry immediately. But no, Spillane purposely strings you along, making you wonder why he doesn’t pursue this new clue, almost to the point that you get frustrated with Hammer, and then he goes there. The art is in knowing how long you can tease the reader before he throws your book in the trash.

Spillane Principle #2: Keep sequels short and to the point.

That’s Sherri Malinou, one of Spillane’s wives, on the cover.

By sequels, I’m not referring to movies like Jaws 2 or Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (I loathe that movie). In storytelling parlance, a sequel is a brief period of reflection and/or planning by the protagonist following a scene with conflict. The idea is that a story is a series of scenes and sequels strung together: conflict-reflection-conflict-planning-and so on.

In the Mike Hammer novels, after a scene of conflict Hammer doesn’t spend a lot of time mulling over his troubles or what to do next. In fact, if anything, the criticism of Hammer has been that he acts too impulsively, with virtually no visible motivation. Clearly this approach doesn’t work for literary fiction, but in the realm of genre, or commercial fiction, it’s nearly a commandment.

Related to this, and perhaps obvious to modern readers, is the idea that your characters shouldn’t take a lot of time getting from place to place. Mickey Spillane, Donald Westlake, and most of the noir writers from the pulp era were among the first to recognize the importance of this. Unfortunately, somebody forgot to tell the TV writers during the 1970s, because if you watch closely at least ¼ of every episode of Hawaii Five-O showed people driving. (I’m convinced the producers were being paid off by auto manufacturers.)

Spillane Principle #3: When your detective discovers an identity—particularly the killer’s—don’t have him reveal it immediately.

In the climactic scene of I, the Jury, when Hammer figures out who killed his best friend, Spillane strings the reader along for a couple of pages. This might seem obvious, but I think that modern TV detective shows have made writers forget the importance of delaying gratification. Even if your story is in 1st person, if your narrator has been forthcoming with thoughts, theories and events throughout the rest of the book, he deserves a few moments of privacy. And it’s at this critical juncture that I believe the detective has earned that privacy.

Doing this allows you to entice the reader to the solution, and it gives the reader an opportunity to solve the case herself. The idea is that if you’ve played fair with the reader, presenting all of the information and clues your detective uses to solve the case, your reader should be able to solve it as well. Creating this brief delay between the detective figuring out whodunit and the summation allows the reader to participate, investing her more deeply in your characters and the story. And if you do it right, and the reader guesses incorrectly, she will paradoxically love and respect you all the more.

Spillane Principle #4: Sex and violence, in their varying degrees, are really the only two colors on the writer’s palette.

This is the Spillane idea I’ve gotten the most out of. When you think about it, all scenes have (or should have) a conflict with tinges of sex or violence in them. Now, by sex Spillane didn’t necessarily mean hardcore, on the rug, chicka-wa-wa screwing; sex can be a kiss, the promise of an embrace, or as little as a flirty exchange. And by violence he didn’t necessarily mean that one character had to pummel another one with a pipe (although this happens, and aren’t we readers glad for the cathartic joy these events bring?); violence can be extremely subtle, like one character nudging another while on a line, a woman’s catty remark about another woman’s shoes, or simply one character’s refusal to do something another character wants.

Thinking of scenes and interactions between characters in this way has, for me, simplified the writing process. I’m not saying it’s easy or that I’ve mastered it (or even think I will). What I’m saying is that approaching the writing of fiction with this metaphor in mind has given me something concrete to gauge my writing against. I think of the sex-violence writing palette metaphor as those slide bars in Photoshop that control color, brightness and contrast. For every scene, at least subliminally, I think about what degree of sex I want to convey, and what degree of violence the scene should have. This idea of Spillane’s, besides the novels themselves of course, is his greatest gift to writers—especially those of us endeavoring to write commercial fiction.

Spillane Principle #5: Be clear about why you write.

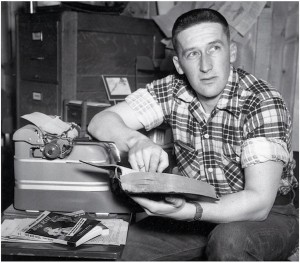

Spillane when he was a young buck. I love how naturally he’s posing, pointing at the book.

I’m not sure if this is apocryphal or not, but allegedly Spillane only wrote when he needed money and spent the rest of his time deep-sea fishing. In a 2001 interview, he told the Associated Press that writing “…is an income-generating job.” Thinking of writing this way, I believe, keeps it clear in the writer’s mind exactly who they’re writing for. It shouldn’t be for yourself. It should be for the reader, the guy or gal who’s going to plunk down $24.95 for your hardcover book.

And even if you don’t care about selling your work, remember that writing is only blank ink on paper or dots on a screen until somebody reads it. As my first writing mentor, Thomas Gallagher, once told me (two weeks before his death), “Chris, writing is communication.” Sounds like something the village idiot would say, but it’s actually a profound point. Until someone takes in your message, processes it and is affected by your words, you haven’t done anything.

I’m saddened by the death of Mickey Spillane because I always thought his fiction was richer and better written than the critics ever gave him credit for, and while he won some awards during his lifetime and was recognized by his peers, the “literati” wrote him off as a hack. This is unfortunate because I believe that in 20 years or so, academics will do serious “studies” of 20th century pop fiction and discover that he was one of a handful of writers who gave birth to modern commercial fiction.

However, I have to admit my feelings of loss aren’t entirely altruistic. I’m also saddened by Mickey Spillane’s death because as soon as my mystery novel, A REAL PIECE OF WORK, was accepted by a publisher, I planned on flying down to Florida and begging him (or fighting him—he was 88, so I probably could have taken him) for an endorsement of my book. That isn’t going to happen now.

Goodbye, Mickey, and thanks for your wisdom—even if you didn’t know you were teaching us. And say hello to Doyle, Hammett and Chandler for me, would you?

Comments (0)