Love Story to Sweetie

WHAT CAN YOU SAY about a 9‑year-old girl cat who died?

That she was bright-eyed. And beautiful. That she loved Breyers blueberry yogurt. And Cabot cheddar cheese. And me. That she was finicky, which I viewed as evidence of her refined sense of taste. Once, when I offered her a piece of Jarlsberg, she batted it across the kitchen. My kitty liked her dairy piquant.

I never learned where I ranked among her favorite things—I might have topped yogurt and cheese, but certainly not shrimp nor the summer sun patch by the sliding glass door. Many times, Sweetie was enjoying a sun patch when I called her to come lie on Papa. She appeared to work out an algorithm of the opportunity costs of leaving the warm spot, concluded it was more sensible to stay put, and lay her chin on the floor as final verdict.

We met—that is to say I bought her—in a pet store in ritzy Scarsdale, New York. “Critter Comforts” was the name. At the front near the checkout was a fenced-in display of cats and kittens—rescued feral cats, discovered living underneath a local orphanage. The display was the veritable bargain bin of house cats. A sign offered incentives (shots, food, toys) to buy one of these implicitly inferior animals—ones lacking papers, pedigree, provenance. But none of these things would have mattered anyway; I’m a sucker for the underdog(cat).

It was mid-morning, shortly after feeding time, and the mothers and their kittens were piled atop each other on carpeted perches, smushed against the wire fence. They were all dead asleep—except one: a gorgeous, green-eyed tabby with minute streaks of orange in her gray-black coat and the stripe pattern of a tiger. Unlike most cats, whose faces broaden out as they get older, Sweetie’s always retained its youthful proportions: big eyes and svelte mouth with a paper-white chin. She stood up tall and gazed at me, and as I reached over the fence, she leapt into my hands.

It was my one and only experience of love at first sight.

I walked her around the store, she ensconced in the crook of my arm, shopping for toys and cat accoutrements. I remember buying her a carpeted stump with a hollow den for sleeping. A carrier. Some catnip mice and what would eventually prove to be her greatest recreational activity, the one at which she was an unmitigated natural: Feather-on-a-Stick. (Feather-on-a-Stick included a game I invented: “Bigjump.” Upon my saying “Bigjump” in a sprightly and encouraging tone, Sweetie would jump to ever-increasing heights and claw the feather to the ground. I once measured her jumping prowess with a yardstick and determined that in order to proportionally replicate her feats, Michael Jordan needed to have a vertical leap of 20 feet.)

A carrier. Some catnip mice and what would eventually prove to be her greatest recreational activity, the one at which she was an unmitigated natural: Feather-on-a-Stick. (Feather-on-a-Stick included a game I invented: “Bigjump.” Upon my saying “Bigjump” in a sprightly and encouraging tone, Sweetie would jump to ever-increasing heights and claw the feather to the ground. I once measured her jumping prowess with a yardstick and determined that in order to proportionally replicate her feats, Michael Jordan needed to have a vertical leap of 20 feet.)

Of course the five dollars per spare feather was outrageous, later prompting in me an irrational desire to win the lottery so I could start my own feather-on-a-stick company and drive this one out of business, but for the moment all I cared about was showering affection on my new writing companion, so I bought everything—including food and food dishes and brushes and bitter apple deterrent spray—as well as three extra feathers.

The cat was my wife’s idea. It was November 2001. After 9/11, I had taken a voluntary severance package from a Manhattan financial services firm, and with Alexas’s blessing was focusing full-time on my writing. Prior to this, I had wedged writing into my days John Grisham-style: before work, during train and subway rides, during lunch alone in the gourmet corporate cafeteria, during soporific meetings to stay awake.

Alexas had insisted on a companion for me partly because of the long hours I would be home alone during the week, but also because a few years earlier I was diagnosed manic-depressive, specifically Bipolar II. Alexas had read about the therapeutic effects of pets on the mentally ill. Getting a cat, she argued, would soothe my own savage beast by giving me something to care for. (It would also prevent my becoming a solipsist, I added.) And for several years this strategy worked—in the early months especially. Between writing stories and submitting them and getting the mail and burning the rejections and flushing the cinders down the toilet, I had kitten duty to attend to, which included being ubiquitous and forthcoming with copious no’s when I caught her biting on electrical cords or scrunching into dangerously tight spaces.

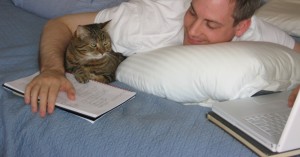

Since my bipolar meds made me tired—even more so during a depressive cycle, which lasted from two days to two months—I took a nap every afternoon. Having always slept flat on my back, I allowed Sweetie to curl up in the V between my legs. Her naptime was invariably shorter, and within an hour I would be awakened by light, exploratory footsteps on me beneath the blanket that gradually worked their way toward my chest, until her sweet face burrowed out from the covers. She blinked, licked my cheek and curled up, purring—all 2 pounds of her—atop my beating heart.

Since my bipolar meds made me tired—even more so during a depressive cycle, which lasted from two days to two months—I took a nap every afternoon. Having always slept flat on my back, I allowed Sweetie to curl up in the V between my legs. Her naptime was invariably shorter, and within an hour I would be awakened by light, exploratory footsteps on me beneath the blanket that gradually worked their way toward my chest, until her sweet face burrowed out from the covers. She blinked, licked my cheek and curled up, purring—all 2 pounds of her—atop my beating heart.

Feather-on-a-Stick, Bigjump, and aquarium fish-watching were her preferred activities in the early years, although we eventually had to get rid of the aquarium. Sweetie had figured out how to flip open the top hatch, trying, albeit unsuccessfully, to catch herself a snack.

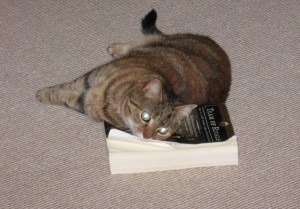

It was around this time that I started to understand the questions and responses implicit in Sweetie’s meows. From the beginning she employed a full palette of cat communication techniques: sharp, plaintive meows with sustained, scolding eye contact (usually used when I had done something wrong, like being away for several hours);  bright, contented chirrups; and the calculatedly adorable “silent meow”—used whenever she wanted my attention but knew I was working. Also in her array of subtle tricks were the “tail hug,” wherein she curled the tip of her tail into the crook behind my knee; the clawless paw-tap; the head-bunt; the flop-down; the eraser-bat (she did not like pink pencil erasers for some reason); the quiet stare, which by its unwavering intensity was her equivalent of shouting; and what I termed the “lah-dee-dah”—her brazenly sauntering across my desk in front of me, usually while I stared out the window or at a sheet of paper in my typewriter. Sometimes she even went so far as to walk across the keyboard.

bright, contented chirrups; and the calculatedly adorable “silent meow”—used whenever she wanted my attention but knew I was working. Also in her array of subtle tricks were the “tail hug,” wherein she curled the tip of her tail into the crook behind my knee; the clawless paw-tap; the head-bunt; the flop-down; the eraser-bat (she did not like pink pencil erasers for some reason); the quiet stare, which by its unwavering intensity was her equivalent of shouting; and what I termed the “lah-dee-dah”—her brazenly sauntering across my desk in front of me, usually while I stared out the window or at a sheet of paper in my typewriter. Sometimes she even went so far as to walk across the keyboard.

I should mention how she got her name. Easy: the day I brought her home, after I had observed her for hours and noticed her sweet, grateful disposition, I said to Alexas, “She’s so sweet,” to which she replied, “That’s it! Let’s call her Sweetie.” And there you have it.

As with all pet owners, we had our share of close calls. Like the time Alexas and I were standing at our 3rd floor apartment window, which was open and screen-less. Sweetie, spying her first bird in the tree outside, sprung for it. Miraculously, I caught her in midair. After that we never opened a window that lacked screens.

Then there was the D.C. Affair.

Sweetie had been in our lives for two or three years when Alexas’ mother invited us down to Washington, D.C. for a long weekend. I wasn’t comfortable leaving the kitty alone, we couldn’t find pet care on short notice, and I was damned if my precious girl was going to be jailed in a kennel, so we brought her along.  Not that this was her first trip. She had gone to the house in Maine, to my sister’s wedding, even to Gettysburg, but something about D.C. freaked her out. (Dubya was in office at the time, so we’ll blame him.) The first day wasn’t an issue because we arrived late in the afternoon, ate dinner, and went to bed. The next morning, however, Alexas and I rose early and took a ferry down the Potomac to Mount Vernon. Sweetie, of course, stayed in the hotel room, where Alexas had set up travel-sized food stations and a litterbox.

Not that this was her first trip. She had gone to the house in Maine, to my sister’s wedding, even to Gettysburg, but something about D.C. freaked her out. (Dubya was in office at the time, so we’ll blame him.) The first day wasn’t an issue because we arrived late in the afternoon, ate dinner, and went to bed. The next morning, however, Alexas and I rose early and took a ferry down the Potomac to Mount Vernon. Sweetie, of course, stayed in the hotel room, where Alexas had set up travel-sized food stations and a litterbox.

When we returned from George Washington’s home, Sweetie was gone. We looked everywhere in the hotel room, scoured the hallways and stairwells calling her name, tracked down the manager, and cross-examined the maid (we had left a prominent DO NOT DISTURB sign on the door)—all to no avail.

Finally, about three hours later, after searching and imagining frightful things, like her being dumped down the laundry chute with the dirty linens, in my greatest Sherlock Holmes moment ever, with Alexas, my in-laws, the manager and the maid rapt before me, I strode to the hotel room window (where I was dramatically backlit), spun around and declared, “Once you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth!” I yanked the mattress off the bed and heaved up the boxspring. There, cowering in a hole in the fabric, was Sweetie. She meowed at me—a half-scolding, half-horrified meow that seemed to say, “Where were you? First you leave me in this little hotel room with no window perch, then you’re gone all day. I’m very upset with you, Papa!” I kissed her and put her in the carrier.

However my and Sweetie’s relationship as Papa and kitty became indelible much earlier than that—within a couple months of getting her.

It was Christmas Day, 2001. The family, including Alexas and me, my parents and younger sister, were spending the holiday at our vacation house in Maine. Two days earlier, a blizzard had cloaked the countryside in a foot of snow.

It’s Christmas afternoon. To give the fire a better draw, my father opens the door to the porch. After a few minutes I notice the door is open and ask, “Where’s Sweetie?” Instantly his face matches the snow outside.

“Jeezis,” he says, “she couldn’t of gotten out! I only had it open a minute or two.”

I go to the door and throw it open. Sure enough, a tottering trail of tiny footprints heads out the door, breaks through the crust on the foot-deep snow, and disappears off the porch. I glance at the outdoor thermometer: 5ºF—scary cold, and if you’re a kitten, deathly cold. It’s three o’clock, which means one, maybe two hours of decent daylight left. Desperate to find her, I run outside in my socks and a sweater.

I knew that adult feral cats were capable of surviving outside in winter, but a 12–15-week-old kitten, alone? Trudging through the snow, I feared the worst, expecting any moment to find her frozen stiff or buried in a deep pocket of snow and suffocated. Her tracks were faint, and a wind was starting to come up, blowing away the loose powder atop the crust. If I didn’t find her soon, I would lose my one and only chance.

Before the wind erased her paw prints, I followed them across our backyard, towards a small gully between our property and the next-door neighbors’. I squatted down and noticed that the snow on the opposite bank was disturbed, like something had clawed its way up. Peering over the bank, I scanned the horizon from her perspective—inches off the ground—and asked myself, “If I were a kitten—cold, disoriented and seeking warmth—where would I go?” The only shelter nearby was a low porch attached to my neighbors’ house.

My family had all gone to the front of the house and were calling the cat’s name, a tactic whose value I questioned, since Sweetie had yet to respond to her name with 100% accuracy. By now my feet were freezing, but there was no time to get my boots. The sun was low in the sky, throwing deep blue shadows across the snow. I went to the porch, dropped to my stomach and crawled partway underneath, a task complicated by my being 40 pounds overweight at the time. I managed to squeeze in about 6’ before my back ran out of clearance. A gray light filtered in from the one side where the snow hadn’t banked against the porch.

“Sweetie? Sweetie, honey, where are you?”

I listened. At first I heard only the wind, but as it subsided I made out the smallest meow. I couldn’t see anything, so I called out again, and she replied again. It was coming from somewhere against the house foundation. I didn’t have a flashlight. I would have to do this solely by ear and feel.

I kept calling to her in the dark and homing in on her cries, which, like a Geiger counter, grew stronger and faster the closer I approached. “Papa, Papa, I’m here,” she seemed to say. Claws were scratching on metal. She was leading me towards one of those metal culverts around a basement window. I groped around, praying I wasn’t about to put my hand into a skunk’s winter nest, reached into the bowl-like hollow, felt a tail, then a wet nose. I pulled her out, backed up and emerged in the half-light with her. She was shivering. I tucked her under my cashmere sweater against my T‑shirt with her head sticking out of the neck hole. My father marched toward us clutching a snow shovel.

“You found her. Thank God.”

“Yeah, let’s go in.”

I spent the next hour with her by the fire, bundling her in warm towels. She was completely still, unbothered by being confined. In fact, she purred and gazed lovingly at me until her eyes became heavy. “You rescued me, Papa,” her sleepy look said. “Someday I’ll rescue you.”

She was, by anyone’s definition, a fraidy-cat, something for which I am probably as much to blame as her genetics. Even 9 years later, even after caring for her when we were away, several of my friends and relatives only ever saw her as a dark blur disappearing into a closet. Some doubted that we even had a cat.

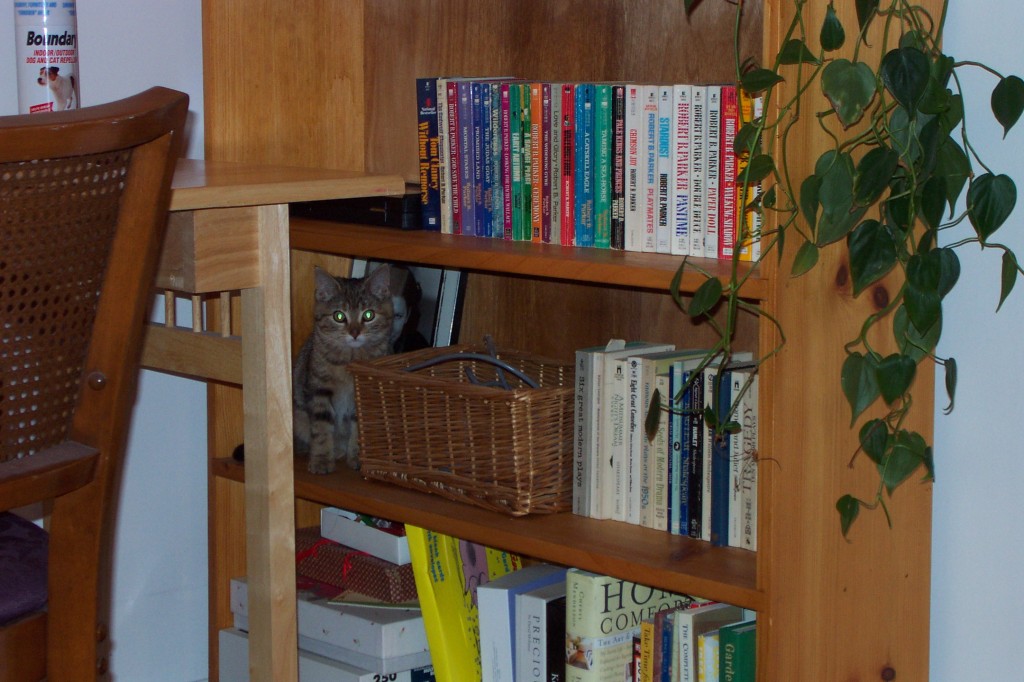

The only two people Sweetie was consistently unafraid of were me and Alexas. Since she died, I have learned that in order for cats to be effectively socialized, they need to be around a variety of people and situations—two things that Sweetie did not get in her critical first months. The apartment was quiet, and, with the exception of the clacking of a typewriter or my swearing at a recent rejection, I too was quiet. This meant that whenever we had overnight guests, or if relatives, the building super or the UPS guy showed up, she went into panic mode, stopping short behind me and staring at the door as it opened. Invariably whoever was there frightened her and she would squat to the floor, elongate herself like a ferret and scurry away—a behavior that struck me as a bit off, since plain-old running was far more efficient—to one of her many hidey-holes. Her Alamo? A bookcase bottom shelf, in the hollow space behind some reference books.

Like other cats, Sweetie had her idiosyncrasies, some adorable, some exasperatingly not. For four years after 9/11, I was an adjunct English lecturer at Baruch College in Manhattan. I routinely came home with piles of papers to grade, which I spread out next to me on the bed. Sweetie would join me, and I quickly discovered that she enjoyed rolling around on certain students’ work more than others’. Studying their names, I quickly deduced the common thread: they were my stoners. When I returned the papers, for fun I sometimes called those students aside.

Like other cats, Sweetie had her idiosyncrasies, some adorable, some exasperatingly not. For four years after 9/11, I was an adjunct English lecturer at Baruch College in Manhattan. I routinely came home with piles of papers to grade, which I spread out next to me on the bed. Sweetie would join me, and I quickly discovered that she enjoyed rolling around on certain students’ work more than others’. Studying their names, I quickly deduced the common thread: they were my stoners. When I returned the papers, for fun I sometimes called those students aside.

“Go easy on the ganja, folks,” I said, to which they incredulously replied, “What? How…how did you know?”

I never revealed my secret weapon: Super Sweetie.

Some of Sweetie’s other habits may not have been unique to her, but they were no less adorable or annoying. Contrary to the conventional wisdom that says you can’t bathe a cat,  from the time Sweetie was a kitten, Alexas and I used a three-bucket system she’d seen on Martha Stewart to wash her. After we dried her in towels, Sweetie retreated to the Alamo for an hour to groom herself and pout, but when she emerged, her coat full and gleaming and redolent of baby shampoo, she strutted back and forth in front of us, basking in our praise: “Oh, Papa, look…look at the beautiful girl!”

from the time Sweetie was a kitten, Alexas and I used a three-bucket system she’d seen on Martha Stewart to wash her. After we dried her in towels, Sweetie retreated to the Alamo for an hour to groom herself and pout, but when she emerged, her coat full and gleaming and redolent of baby shampoo, she strutted back and forth in front of us, basking in our praise: “Oh, Papa, look…look at the beautiful girl!”

Not so beautiful was her predilection for snacking on bugs; disgusting is what it was, but Alexas assured me that “it’s what cats do.” I probably shouldn’t complain, though; her taste for insects may be why I never saw a single cockroach in our apartments. Another habit of hers was annoyingly sneaky, yet for some reason I respected her for it. Before I would acquiesce to give her some “cheeser” or a piece of shrimp, she had to be standing on the dining table rug, not on the kitchen floor. It was still begging, but at least this way I wouldn’t trip over her. While she started out complying with the new rule, she gradually became a living slippery slope, worming her way out half an inch here, two inches there, until only the tip of her tail was on the rug.

Another habit of hers was annoyingly sneaky, yet for some reason I respected her for it. Before I would acquiesce to give her some “cheeser” or a piece of shrimp, she had to be standing on the dining table rug, not on the kitchen floor. It was still begging, but at least this way I wouldn’t trip over her. While she started out complying with the new rule, she gradually became a living slippery slope, worming her way out half an inch here, two inches there, until only the tip of her tail was on the rug.

“Sweetie,” I’d say.

She’d chirrup in reply, as if to say, “Hey, I am on the rug. See my tail, Papa? See? Now how’s about some of those shrimps?”

By age three, she began to have problems keeping her food down. In other words, she puked—three or four times a day. So much that  we had to buy paper towels in bulk. Eventually we had to remove all wet food from her diet. Nothing but the oatmeal of cat food: Science Diet Sensitive Stomach. Vet appointments were useless, the trauma often provoking more puking while yielding no answers as to its cause. There were stomach medications, thyroid medications and more.

we had to buy paper towels in bulk. Eventually we had to remove all wet food from her diet. Nothing but the oatmeal of cat food: Science Diet Sensitive Stomach. Vet appointments were useless, the trauma often provoking more puking while yielding no answers as to its cause. There were stomach medications, thyroid medications and more.

When she turned five or six, the Night Crazies started.

From the time Sweetie was a kitten, Alexas and I had let her sleep with us, always without incident. I sleep on my back, with my sock-covered feet sticking out from beneath the covers, and apparently, after years of coexisting with them, Sweetie suddenly found my feet an irresistible temptation. At three o’clock in the morning, she began to pounce on them and bite them. I’m ashamed to admit that I never learned to react with saintly kindness and understanding; instead, I would yell death threats, grab the nearest magazine and chase her out of the room.

Why she did it, I have no idea. She might have been startled out of a deep sleep and seen my long, gaunt feet towering over her (a scary prospect if you knew my feet), or perhaps like her Papa she was having violent nightmares, waking up and lashing out at the nearest threat. Or, maybe she was just bored and biting my feet was the most fun a cat could have at 3 a.m. Whatever the reason, as she grew older this tendency became more pronounced, as did her waking up from naps disoriented and hissing.

Eventually we had to ban her from the bedroom at night, which may have stopped the biting but didn’t change her other night behavior: confused yowling, door-scratching, and growling at things outside. Several times Alexas awoke to see what was the matter and to comfort her, and she never saw what, if anything, Sweetie was reacting to outside. She appeared to be seeing things. Or not seeing them, as in the case of her begging to have food put in her dish when it was already full.

Her increased vocalizing continued during the day, too, becoming so frequent and irritating that several times I snapped at her to “Stop it!” or “What is it?”—as if she could tell me. She also became more clingy, wanting to lie on me every chance she got, and at first I welcomed her attachment. My fondest memories of Sweetie are of my writing in bed and her crawling up to lie on my stomach while I wrote with the clipboard resting on her. She seemed not only content to have to share me with my clipboard and pencil, but I think she took a little pride in her role as clipboard-holder, knowing that she was helping Papa.

Her increased vocalizing continued during the day, too, becoming so frequent and irritating that several times I snapped at her to “Stop it!” or “What is it?”—as if she could tell me. She also became more clingy, wanting to lie on me every chance she got, and at first I welcomed her attachment. My fondest memories of Sweetie are of my writing in bed and her crawling up to lie on my stomach while I wrote with the clipboard resting on her. She seemed not only content to have to share me with my clipboard and pencil, but I think she took a little pride in her role as clipboard-holder, knowing that she was helping Papa.

Many, many times she saved me, too, hopping on the bed and walking tentatively over to lie on me. It saddens me to remember that there were a few times when I pushed her away. Sweetie could always sense when I was in a depression and would stay close to me for hours, days, weeks. Once, I was lying on my back, staring at the ceiling, seriously considering the best way to commit suicide, when Sweetie crawled on my chest purring, sat down and licked my nose. One could call it coincidence, but I know better. More than once, that little cat was an instrument for higher forces. More than once, Sweetie saved my life by giving me something tangible—herself—to love.

Sweetie could always sense when I was in a depression and would stay close to me for hours, days, weeks. Once, I was lying on my back, staring at the ceiling, seriously considering the best way to commit suicide, when Sweetie crawled on my chest purring, sat down and licked my nose. One could call it coincidence, but I know better. More than once, that little cat was an instrument for higher forces. More than once, Sweetie saved my life by giving me something tangible—herself—to love.

Which is why it broke my heart when the attacks started. One morning after Sweetie had been up all night growling at imaginary threats outside, Alexas mimicked for me the sounds the cat had made, and Sweetie tore across the room towards Alexas. I jumped in front of her, and the cat clawed my leg. Shouting at her, fending her off with a chair like a lion-tamer, I eventually got her to settle down. Later I learned that her behavior was known as “redirected aggression.” She had become riled up by real or imaginary threats, but being unable to attack the interloper, she took out her aggression on us instead.

In my heart I knew that my own mood swings, which are erratic and often unprovoked, had contributed to her perpetual nervousness and tension. More than one person in my life has said that being around me is tantamount to walking on eggshells, through a minefield. So I could almost understand why, after 9 years, she finally snapped and attacked me. Maybe I deserved it. Deciding that it was an anomaly, I forgave her.

Our final morning together began peacefully, like the attack at Pearl Harbor. I awoke at my usual time—5:00 or 5:30—made coffee, wrote, showered and dressed. It was a few minutes before 7:00 when Sweetie hissed out at the patio. The sliding door was open with the screen in place. Sweetie was pressed against the screen, staring and growling at the neighbor’s cat. She had never done this before; neither at neighboring dogs nor cats. I let her drive the animal away, said, “Okay, Sweetie, you won,” then closed the sliding door. Within seconds, she sprang at me, screaming, clawing, biting. She raked my arm, rent my T‑shirt down the chest. I threw her off, and she came at me again, this time leaping at my neck. I slapped her in midair, hitting her hard in the mouth (and puncturing my hand on her fangs), knocking her against the kitchen drawers. Momentarily stunned, she poised herself for another attack. I reached for the chair and swung it between us. I shouted at her, she backed away, and I went into the bathroom.

As I cleaned and dressed my wounds, I thought about how ferocious this second attack had been, and my instinct told me something was wrong with her. A wave of nausea coursed through me: I would have to put her to sleep.

What were my other choices? Continue to live with the cat, but in constant fear of another, even worse, attack, and in fear that I would have to hit her even harder next time, when hitting her once had already made me sick? Send her to a “home” for troubled animals, if such a thing even exists? Consult an array of pet therapists? Put her through a long (and expensive) battery of tests, further traumatizing her with stays in hospital kennels, and all without any guarantee that it would restore her to her sweet self?

Observing her behavior over time, it was clear to me that she was suffering from something, or a combination of things, that caused the puking, the nervousness, the hallucinating, the yowling, and the aggression. However, as is often the case in life, the most ethical and humane option was perforce the most difficult one.

Twenty years earlier, I had taken a course on Ethical Issues in Medicine. As an argument in support of euthanasia  I posited the idea that in addition to preventing her own sustained suffering, a dying patient has the right to determine how she will be remembered by others. In most cases she would not want her suffering to erode others’ good memories of her. In the case of Sweetie, I felt that she had a right to be remembered by Alexas and me for her beautiful attributes, not for making us fearful in her final days.

I posited the idea that in addition to preventing her own sustained suffering, a dying patient has the right to determine how she will be remembered by others. In most cases she would not want her suffering to erode others’ good memories of her. In the case of Sweetie, I felt that she had a right to be remembered by Alexas and me for her beautiful attributes, not for making us fearful in her final days.

I told Alexas of my decision, instructing her not to try and talk me out of it. The pain that clutched my stomach was bad enough to go through once; I wasn’t going through it a second time.

I think Sweetie sensed my decision, but she wasn’t fearful about it. Almost as if to console me for having to make it, she walked over to me and gave me a sustained tail-hug. I lay a hand on her side, and we sat there for some time. Inexplicably, I had the feeling that Sweetie had been trying for quite a while to communicate to me that she was sick and was now relieved to have finally gotten through to me.

On the way to the vet with Sweetie in her carrier, I talked to Alexas about the various options, saying “the egg” instead of the cat’s name because I didn’t want to upset her. Alexas agreed that we had only one choice.

The first available appointment was at 10 o’clock. Still not certain about the decision, I drove to a church, went in and prayed. I felt like an executioner and wanted some sense that I was doing the right thing.

When I opened my eyes, I had the gut feeling, the knowing, that Sweetie was indeed suffering, that she in fact had a brain tumor. Then, at that precise moment, the church bell tolled nine times.

Nine times. Nine lives. Nine years old.

What else I could ask for in terms of confirmation?

The veterinarian spoke with us for half an hour, during which we described Sweetie’s behavior of the past several months. He concurred that there was most likely a brain tumor at work. The kindest thing we could do for her was to painlessly end her suffering. We told him to make the preparations.

When we went into the examination room, Sweetie lay stretched out on a soft quilt that was tucked in around her back to keep her warm. The doctor had administered a heavy sedative, so while she couldn’t move, he said, she could still hear us. He and the nurse departed so we could say our goodbyes.

Before going in, I had made Alexas promise that we wouldn’t break down in Sweetie’s presence. Although the cat was sedated, I knew she would still be able to sense our fear or sadness, and I was determined to make her final moments peaceful.  I placed a hand on her and talked softly to her. “Papa loves you, Sweetie,” I said. “Papa loves you.” I told her how much she had meant to me, and I thanked her for nine wonderful years of companionship—years that I needed her more than I ever realized. Several times as I spoke, Sweetie’s muscles twitched; Alexas said this was her way of communicating back to me, and I think she’s right. Then I sang a song to Sweetie, a lullaby I had made up and sung to her when she was a kitten:

I placed a hand on her and talked softly to her. “Papa loves you, Sweetie,” I said. “Papa loves you.” I told her how much she had meant to me, and I thanked her for nine wonderful years of companionship—years that I needed her more than I ever realized. Several times as I spoke, Sweetie’s muscles twitched; Alexas said this was her way of communicating back to me, and I think she’s right. Then I sang a song to Sweetie, a lullaby I had made up and sung to her when she was a kitten:

I kissed her, then Alexas kissed her, and the veterinarian returned. He gently shaved her back leg near the ankle, found a vein and injected the strong barbituate. Alexas and I stood at the side of the table, tightly holding hands and trembling, but not crying, while the vet checked for breathing and a pulse. There were neither.

We stayed with her for a few more minutes. What I most vividly remember about those final moments is how warm she still was. I pet her belly—something she almost never let me do—expecting, I think, she would suddenly come back to life. She didn’t. I kissed her head for the last time and walked out, leaving instructions with the nurse to donate Sweetie’s carrier to another family.

And then, outside in the warm and breezy summer morning, I did something unexpected, something I hadn’t done since my grandfather died, much less in public.

I steadied myself on the walkway railing, stomped my foot at the gods, and wept.

Comments (38)