One Decision that Changed My Life for the Better

Last weekend, I attended a surprise party for my younger sister’s 50th birthday. The party, hosted by her husband and best friend, was a great success, mostly because she never had a clue about it. During the party, I found myself among some of my sister’s friends from high school. These women were a couple class years behind me, and most of them hadn’t seen me since then. One of her friends was chatting with me and other people from our school when, out of nowhere, she blurted out to the other women at the table, “Chris has not aged a year! Not a year! He looks exactly like he did in high school!” She said this in an awestruck tone, got up and walked away shaking her head.

After the party, I kept thinking about the woman’s compliment, and I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t deeply flattered. Of course I have aged since high school, but perhaps not as quickly or as severely as others. I’ve gained weight (I no longer have the 3% body fat I had back then); my hair is thinner and silver now, instead of the lush auburn brown it once was; and over the past 33 years I’ve struggled with excesses and addictions including marijuana and alcohol. (Thankfully, I’m now completely sober, and have been for almost three years.)

I continued to think about the woman’s compliment during the week, when I engaged in my fitness regimen, which includes some variety of the following: strength training, running, rowing, lap swimming, tennis, hiking, mountain climbing, golf, cross-country skiing (in season), and flexibility and pliability work. I also thought about my recent vacation alone to the seashore, where I—sun-kissed, muscular and dripping wet—had a walking-out-of-the-surf moment akin to Daniel Craig’s in the James Bond movie Casino Royale.

As I relaxed at the seashore, engaged in my fitness regimen, and mused about the compliment that I haven’t aged, I realized that the life I’m living now is largely because of a book I read a long time ago.

When I was 14, I stumbled upon a book in my junior high school library that changed my life in innumerable ways. I can’t remember the book’s title or author, but it was basically an introduction to Ancient Greek philosophy, with emphasis on the teachings of Plato. One of Plato’s ideas (which I later learned was in his Republic) made a deep impression on me. Plato said that the Ideal Man (or citizen) developed both his intellect and his physical body to their highest potential, and that the two are balanced; he is as strong and physically capable as he is smart and intellectually well-rounded; he is a scholar-athlete. By exercising the body and cultivating the mind through study, the Ideal Man eventually brings the two elements—physical and intellectual—“into tune with one another by adjusting the tension of each to the right pitch.”

I can still remember exactly where I was when I read that. I was sitting alone on the school bus, riding through a neighboring development on my way home. It was an early summer afternoon, close to the end of the school year, and I laid the book on my lap and thought about this idea.

Plato, recalling the teachings of his teacher, Socrates, explained why it was critical that a person should develop both the physical and intellectual: “Excessive emphasis on athletics produces an excessively uncivilized type, while a purely literary training leaves men indecently soft.” He also said that while there were many men who were intellectually developed, and while there were many who were physically developed, there were very few men in the world equally developed in both areas. In other words, the Ideal Man was rare.

This idea was extremely attractive to me at the time. I liked the notion of distinguishing myself somehow, of being special, a rarity. While I was very smart and fairly athletic (baseball, tennis, swimming, horseback riding, Boy Scouts), I wasn’t the smartest person among my friends, and I wasn’t the most athletic or physically developed either. I had a friend (and still have) who was intellectually gifted and showed incredible aptitude for computers. I had another friend who was an avid weightlifter and bodybuilder (and still is, I believe). But—and this is why Plato’s notion of the Ideal Man was so attractive to me—I didn’t know anyone who was both.

That afternoon on that bus, I made a decision, a decision that I now see did more to positively influence my life than any other. I decided I was going to become an Ideal Man—one whose intellectual and physical assets and capabilities are balanced and reach their highest potential. As someone who was very good at coining new lingo at the time, I even came up with my own term for this: “rugged intellectualism.” I decided to make myself into a rugged intellectual.

After school that day I set up a small “gym” in the unfinished basement of the raised ranch where we were living, and I started immediately with body weight exercises: pushups, sit-ups, pull-ups, etc. I filled two gallon milk jugs with stones and lashed the jug handles to a broomstick to create a temporary, makeshift barbell. Soon I got a weight set, bench and heavy bag and really started to make progress on my physique, so by the time I was 17, relatives who hadn’t seen me in a while didn’t even recognize me. I played tennis and baseball in high school, and I also did track.

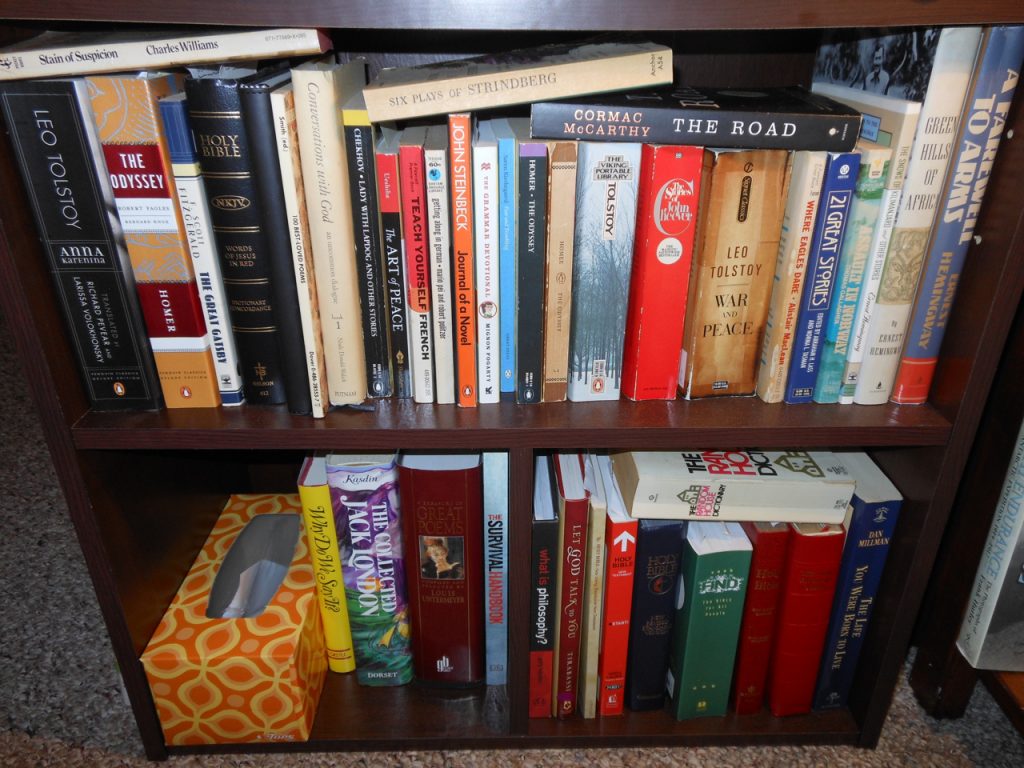

When I got to college, I immersed myself in my studies as never before, starting as a forensic chemistry major and eventually switching to philosophy and history. I had loathed high school—endlessly being told what to do, when to do it, what to study, and the pointless hours of “homework”—but in college, where I was encouraged to be self-directed and self-disciplined—I positively bloomed. In addition to my required coursework, in my sophomore year (when I knew I was going to become a writer) I set out to read as many of the classics as I possibly could. I realized I would probably never again have as much time for leisure reading as I had in college, so I read the classics every chance I got.

Near my college in Boston, there was a bookstore (I think it was one of the now-defunct B. Dalton Booksellers), which had an amazing selection of quality, inexpensive Signet and Penguin paperback classics. Each Friday evening, I would take one of my girlfriends to dinner and the movie theater next door to the bookstore, but before going to the movie, I would buy myself 4-5 new classics. I set myself a goal of finishing one every two days, but some (like Candide and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) I tore through in an afternoon, while others like Anna Karenina, took me a solid two weeks to finish. I can still remember the way the steeplechase scene in Anna K. made my heart pound with anxiety for Anna and Vronsky, the pity I felt for Madame Bovary when (spoiler alert) she kills herself by poison, the nightmares I had while reading the first 100 pages of Dracula, the motivation I felt to write when I read Jack London’s Martin Eden, and the wave of admiration and envy that washed over me when I read Fitzgerald, Hemingway, or Steinbeck. I still have dozens of the 200-plus classics I bought back then.

I went on to reach my highest potential intellectually in college, graduating summa cum laude (5th in my class of 750) and Phi Beta Kappa, but physically I fell down in a major way. Idolizing Jim Morrison and Axl Rose, I drank way too much (sometimes waking from blackouts in Boston alleys), smoked way too much marijuana, got involved with too many girls, and did very little athletically.

Unfortunately, this trend continued on and off through my twenties into my early thirties, when I was trying to get established and choose my career path. I was a newspaper reporter for a few years, then a high school teacher, then a software company co-founder, then a corporate communications manager, then a college instructor, then a speechwriter—and all the while I was developing my fiction-writing skills.

Then, about 20 years ago, my wife encouraged me to quit my lucrative job with Merrill Lynch to focus full-time on my fiction. I had just returned from a friend’s wedding in Las Vegas and looked at pictures of myself at the Grand Canyon. I was fat. I mean fat—especially for a guy who, just 15 years earlier, had had 3% body fat and the build of a virtual decathlete. I was fat and didn’t like it at all. It simply didn’t fit with the vision I’d had at 14 of becoming an Ideal Man. Around this time, I also developed a herniated disc in my lower back from too much sitting and a sedentary lifestyle. So, I bought an expensive elliptical trainer and joined a gym. I started hiking, cross-country skiing and playing a little tennis again, and I weaned myself off the “comfort foods” of my youth.

Through my 30s and 40s I kept up my intellectual pursuits, although because I was also writing my own books, I didn’t have time to read a classic novel every other day like I had in college. Instead, I kept (and still keep) a pile of a dozen books at my bedside and finish one or two a week. In the last 20 years I’ve read probably 20 books that I consider game-changers or works whose ideas have directly benefited me. These include Mastery, Atomic Habits, War and Peace, The Odyssey, The Bible, Wishes Fulfilled, and Tom Brady’s The TB12 Method.

The truth is, living up to that decision I made at 14 years old, trying to achieve balance and my highest potential both intellectually and physically, has been a 37-year struggle. There have been a few occasions along the way when the two lines have intersected (in economics, this is called equilibrium)—when I’ve managed to bring the two “into tune with one another by adjusting the tension of each to the right pitch”—but usually achieving my peak intellectually has required me to sacrifice some on the physical scale, and vice-versa. For example, when I’ve been in the home stretch of the final draft of one of my novels, I’ve had to sacrifice sleep, workouts, food, companionship—heck, even sunlight—to get the work done. And when I’ve been working out intensely every day (say to train to climb a mountain or to prepare for X-C ski season), I’ve written fewer pages on those days and read fewer books in my leisure time.

Which brings me to recent days—completely sober; walking out of the surf, tanned, cut and dripping wet; receiving a compliment from a woman that I haven’t aged since high school; and receiving compliments from other women at my sister’s party about how much they’ve enjoyed my novels—and I’m taken back to that afternoon on the school bus when I decided to become an Ideal Man, and I see that much of my life today resulted from that one decision.

Today I look at my life, and I see that I’ve done it. The intellectual and physical sides of my life are balanced and in tune with each other. While many men my age are struggling with weight issues, heart problems, hypertension, back issues, joint problems, diabetes and/or addictions, I’m in the best shape of my life since I was 17. (True story: the last time I saw a doctor, while reading my chart and seeing my pulse and blood pressure stats, he said, “Excuse me, Mr. Orcutt…are you a triathlete?”) Having taken medication for my mental health for almost 20 years, I now take zero medications—only the occasional aspirin or ibuprofen.

And while I know a few men in very good physical shape, their intellectual lives and achievements have languished. I, on the other hand, have been a lifelong learner, constantly seeking out new ideas and methods to improve my results, and constantly pushing myself intellectually to do more and achieve more.

Today, I view my body not merely as a sack of protoplasm that carries my brain around, but rather as the machine that makes good operation of the brain possible. I’ve learned that when I’m in great physical health—particularly cardiovascular health—I’m able to think more clearly, and I can write better and for longer stretches. I’ve learned that maintaining the physical machine is essential for writing well—especially for the endurance writing that I do of long novels.

I’m feeling a great deal of gratitude lately for finally achieving this balance, and I want to thank my 14-year-old self for it. Not only did my 14-year-old self have the curiosity to seek out, read and think about these ideas of Plato’s, be he also had the wisdom to recognize a great, life-changing idea, and the self-discipline and the resolve to decide to make himself in that image. That one decision has done more to positively influence my life ever since than anything else.

So, thank you, Plato, and thank you, 14-year-old Chris Orcutt.

–

Comments (0)