Only Have Time for Essentials

“At 46 one must be a miser; only have time for essentials.”

— Virginia Woolf, diary, 3/22/1928

I stumbled upon this quotation earlier this week. What struck me most about it was that it expressed a thought I had back in February, when I turned 46 myself, although my version of the thought at the time was admittedly less eloquent.

I said to myself, “Chris, you’re 46 now. You don’t have time for bullshit anymore. You don’t have time for ephemera. You can only spend time with people you truly enjoy, and you have to cut out of your life all people and activities that either don’t make you feel good or that sap your time and energy. Your writing is paramount.”

Over the years I had already winnowed my friends to a select few whose company I loved. Seven or eight years ago, I stopped watching cable TV, with its relentless commercials and anxiety-inducing 24-hour news. I stopped doing all familial “obligations,” which I had found stressful reminders of the passing of time—time I should be writing. I let myself drift away from past acquaintances who had become burdens to me. And, this year, I stopped participating in social media. In fact, I only go online now every other day, to do book-related research or answer emails.

Getting off social media has been a terrific boon for my writing. No longer posting photos or writing about something that happened to me, moments after it happened, has made me reserve my need for self-expression for my books. I’m no longer dissipating my energies by spending hours online trying to promote my books and my “brand.” I’m no longer feeling the perpetual sense of discontent about my life and the state of my writing career that I felt when I had to wade through every other so-called writer’s “look at me, look at me” crap.

My friend Jason Scott has likened my new approach to a samurai sword-maker: I’ve shut myself off from most of modern society to live in the mountains forging, hammering and tempering steel into swords, day in and day out. This is an accurate analogy.

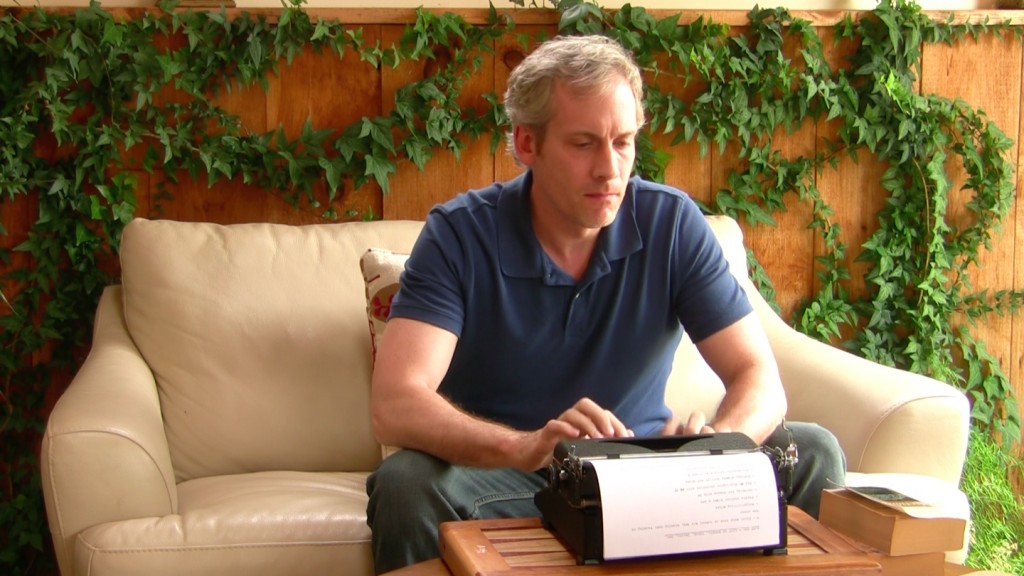

This week I returned from a 3‑week writing sojourn in the Green Mountains of Vermont. I’d always wanted to shut myself off from everyone and everything for a while and see what came from the experience. The house—my friend’s vacation house, high in the mountains—didn’t have internet access or even a telephone. (To make any calls, I had to drive down the mountain to a town where I could get a cell signal.) There was satellite TV, but the only show I watched was Little House on the Prairie, in the afternoons a few days a week. I ate healthily, exercised daily using my TRX, and meditated. I did some filming of the experience with an HD camera Jason gave me. Most importantly, however, I wrote, on my Royal manual typewriter or in longhand (making photocopy “backups” of my work at the local library), and spent the long moments between sentences staring out at nature: trees waving in the wind, rain pouring down, rainbows forming, turkeys foraging on the edge of the woods, and, once, a black bear strolling across the lawn at dusk.

Studying nature this intensely and reading and meditating on a short book on aikido, The Art of Peace, reminded me of a couple of principles regarding creativity. These are ideas that I learned either in my reading of Walden and other philosophy years ago, or when I was a Boy Scout and spent whole days in the woods, but which principles I had forgotten:

Nature is in a constant state of creation, but it never stops to contemplate how its latest creation (the new blade of grass, the spider web, the rainbow) will be received. Nature just creates and moves on. Nature never ceases. Nature focuses on only the truly essential—the creation and perpetuation of life. Nature doesn’t waste time.

The book I’m writing now is a memoir about my life when I was 16. Of my three weeks in seclusion in Vermont, I spent most of that time recalling events from 30 years ago.

Believe it or not, it was very stressful work. Why? Because I was forcing myself to relive uncomfortable emotions related to situations with people I had either loved or hated. There were a few days when I recalled events so painful, it turns out I had blocked them out for 30 years. On one of these evenings, the feelings I was reliving were so painful, I broke down and had three beers—this, after a year of sobriety unfortunately.

On balance, however, the Vermont sojourn was a great experience for me, and the most important thing I learned is this: I don’t want a lot of what modern society has to offer, and usually I don’t need it either. I truly came to understand what Henry David Thoreau meant when he advised people to “simplify, simplify, simplify.”

I’m 46 now. I only have time for essentials.

Comments (0)